Archaeologists unearth unusual find inside Tulum cave

A pre-Columbian apparatus that could be of great use today — a system for catching rainwater — has been found in the archaeological zone of Tulum, Quintana Roo. However, this one apparently wasn’t used as a catchment, since it was found inside a cave.

The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) announced the discovery this week of a chultún, a bottle-shaped structure used in Maya culture.

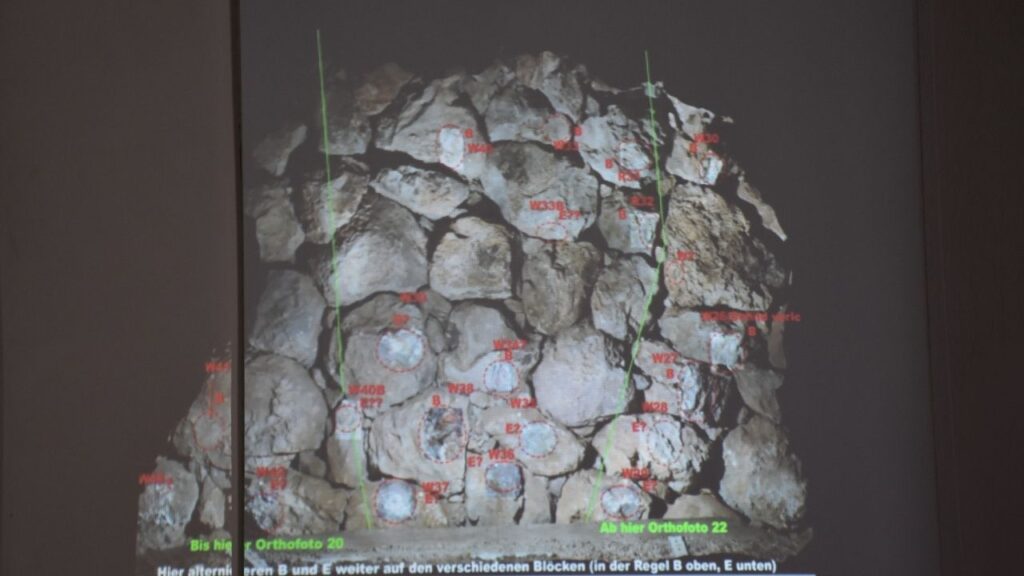

It is the only structure of its type that has been found “indoors” at the Tulum archaeological zone. Located inside a chamber of the cave tabbed Building 25, or Casa del Halach Uinic, the chultún measures 2.48 meters (8.1 feet) in diameter and 2.39 meters (7.8 feet) deep.

According to field manager Enrique Marín Vázquez, the structure “is made up of a layer of ground coral, 1 to 2 centimeters thick, which formed part of the soil surface, and underneath we found reddish clay.

Inside, fillings of medium-sized stones, thick layers of pure ash were found and, in the deepest part, we unearthed human bone remains and burned stones.”

Officials said the discovery could correspond to the first occupation of the site, prior to the Late Postclassic period in Mesoamerica (1250-1521).

The finding occurred during work being carried out by the Program for the Improvement of Archaeological Zones (Promeza).

It is the latest notable archaeological find inside the cave, which was blocked at its entrance by a large rock, on top of human remains, before it was uncovered in December 2023.

The cave has unearthed a trove of archaeological finds, such as the remains of 11 people believed to have been members of an upper class.

José Antonio Reyes Solís, the coordinator of the Promeza research project in Tulum, said two chultúns were previously found outside, and both functioned as catchments.

The latest find, he added, “shows a striking difference” from the other two: Not only was it found inside, but “it has no signs of having stored any liquid,” he said. “Rather, it is believed, it functioned as a storehouse for food and plants, and later, had a ritual use.”

The human remains found are in the process of being investigated, he added.

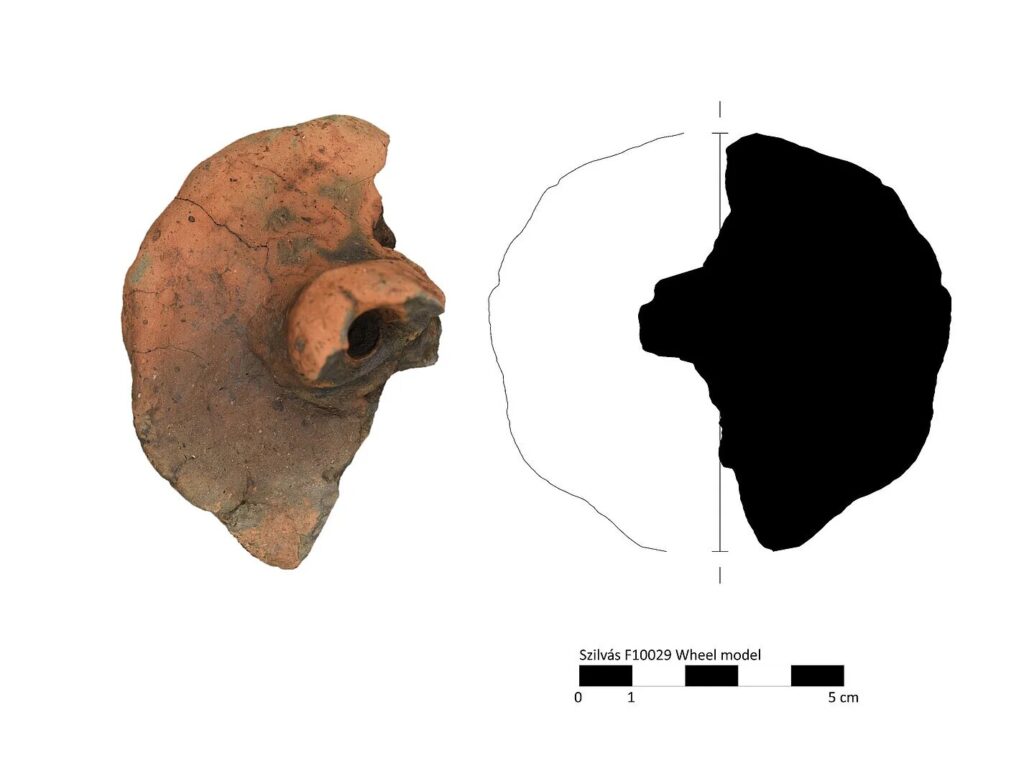

One theory is that they were three infants whose bodies were buried with other materials, such as deer antlers, shark teeth and shell earrings.

INAH is working on a virtual tour that will showcase the recent cave findings at the Tulum National Park.