Japanese scientists ‘reawaken’ cells of 28,000 Old woolly mammoth

Her name is Yuka: an ancient woolly mammoth that last lived some 28,000 years ago, before becoming mummified in the frozen permafrost wastelands of northern Siberia.

But now that icy tomb is no longer the end of Yuka’s story.

The mammoth’s well-preserved remains were discovered in 2010, and scientists in Japan have now reawakened traces of biological activity in this long-extinct beast – by implanting Yuka’s cell nuclei into the egg cells of mice.

“This suggests that, despite the years that have passed, cell activity can still happen and parts of it can be recreated,” genetic engineer Kei Miyamoto from Kindai University told AFP.

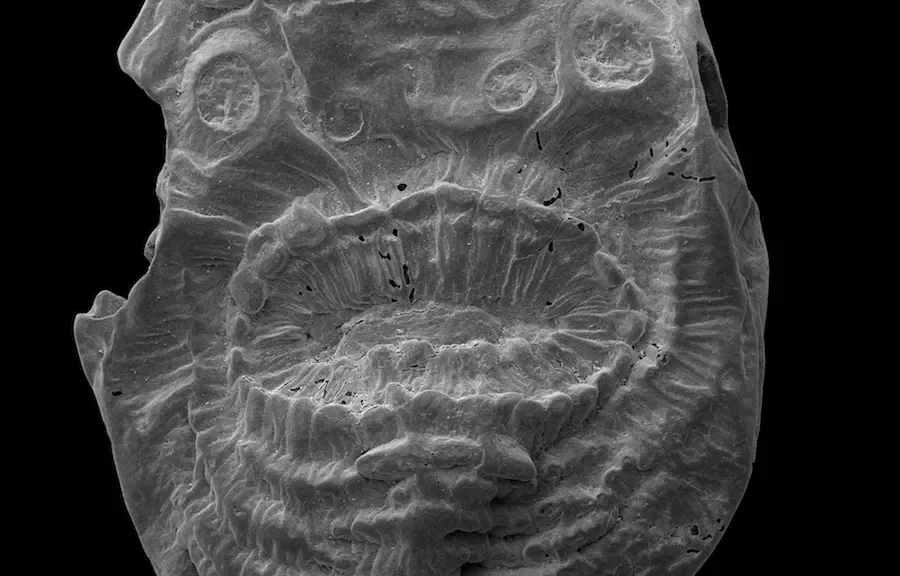

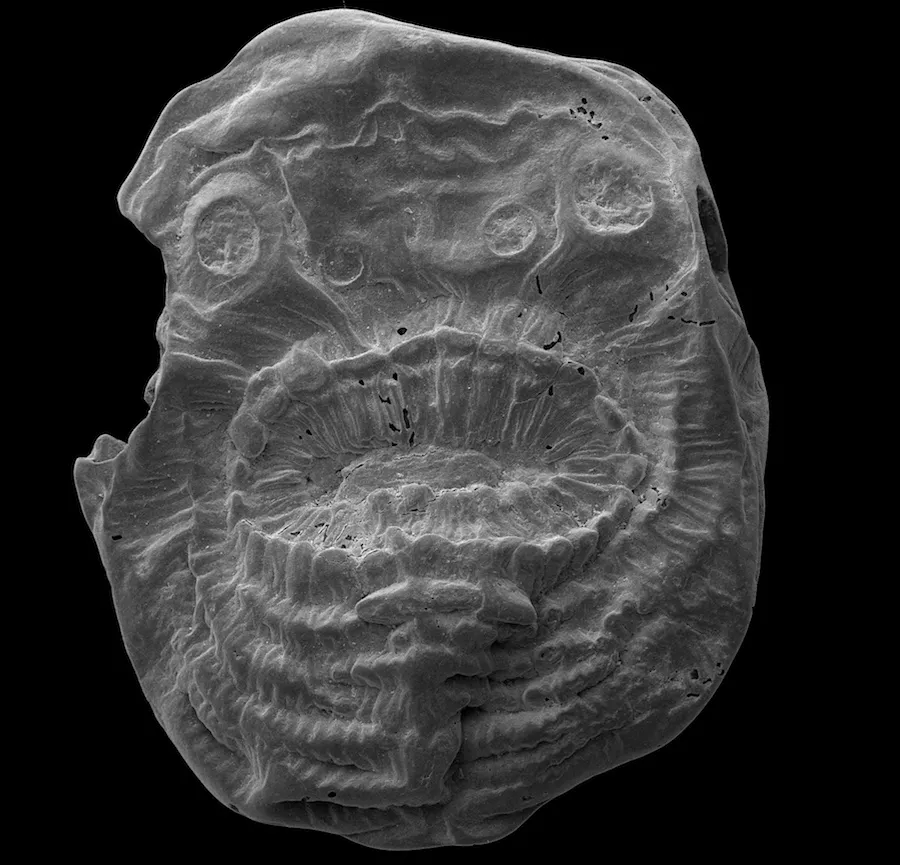

In their experiment, the researchers extracted bone marrow and muscle tissue from Yuka’s remains, and inserted the least-damaged nucleus-like structures they could recover into living mouse oocytes (germ cells) in the lab.

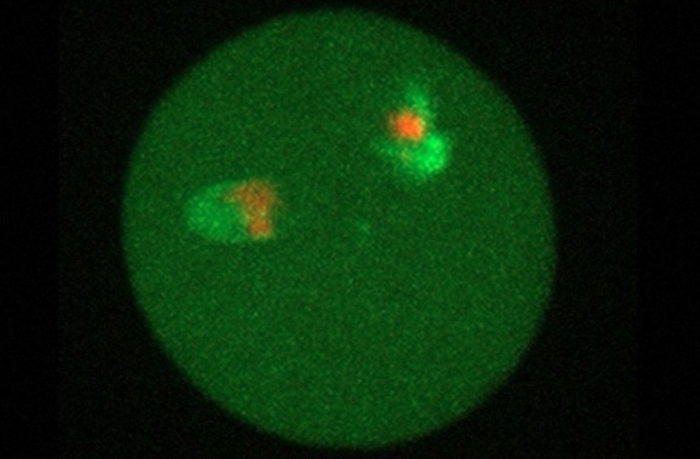

In total, 88 of these nuclei structures were collected from 273.5 milligrams of mammoth tissue, and once some of these nuclei were injected into egg cells, a number of the modified cells demonstrated signs of cellular activity that precede cell division.

“In the reconstructed oocytes, the mammoth nuclei showed the spindle assembly, histone incorporation, and partial nuclear formation,” the authors explain in the new paper.

“However, the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confirmed.”

Despite the faintness of this limited biological activity, the fact anything could be observed at all is remarkable and suggests that “cell nuclei are, at least partially, sustained even in over a 28,000-year period”, the researchers say.

Calling the accomplishment a “significant step toward bringing mammoths back from the dead”, Miyamoto acknowledges there is nonetheless a long way to go before the world can expect to see a Jurassic Park-style resurrection of this long-vanished species.

“Once we obtain cell nuclei that are kept in better condition, we can expect to advance the research to the stage of cell division,” Miyamoto told The Asahi Shimbun.

Less-damaged samples, the researchers suggest, could hypothetically enable the possibility of inducing further nuclear functions, such as DNA replication and transcription.

Another thing needed is better technology. Previous similar work in 2009 by members of the same research team didn’t get this far – which the scientists at least partially put down to “technological limitations at that time”, and the state of the frozen mammoth tissues used.

To that end, the researchers think their new research could provide a new “platform to evaluate the biological activities of nuclei in extinct animal species” – an incremental progression to perhaps one day, maybe, seeing Yuka’s kind roam again.

The findings are reported in Scientific Reports.