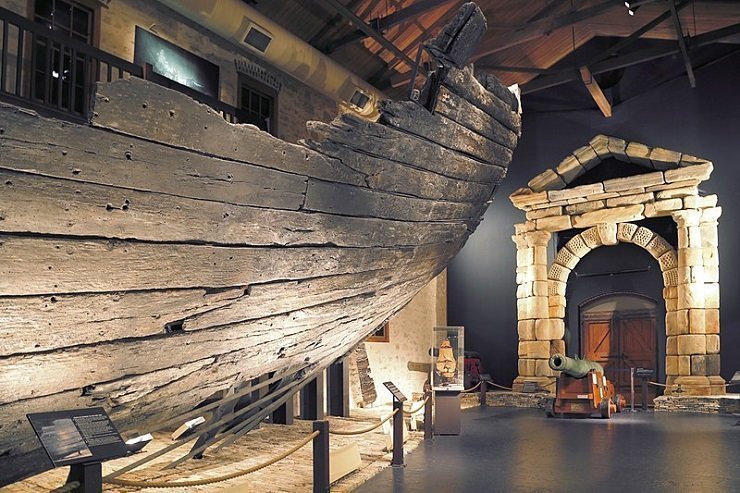

World’s Oldest Intact Shipwreck Found at the Bottom of the Black Sea

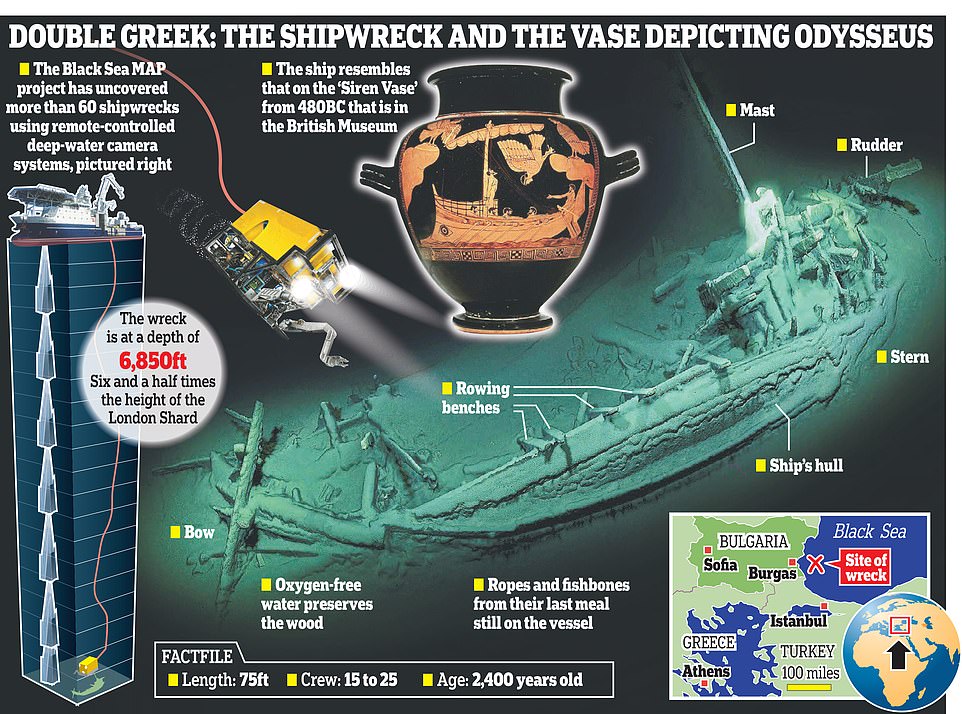

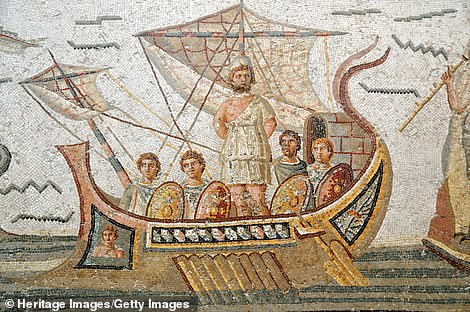

The oldest intact shipwreck ever found has been discovered at the bottom of the Black Sea. The 75ft Greek trading vessel was found lying whole with its mast, rudders and rowing benches after more than 2,400 years. It was found in a well-known ‘shipwreck graveyard’ that has already revealed over 60 other vessels. During the most recent exploration in late 2017, the team discovered what has now been confirmed as the world’s ‘oldest intact shipwreck’ – a Greek trading vessel design previously only seen on the side of ancient Greek pottery such as the ‘Siren Vase’ in the British Museum.

The ship, found 1.3 miles under the surface, could shed new light on the ancient Greek tale of Odysseus tying himself to a mast to avoid being tempted by sirens. The vase shows Odysseus, the hero from Homer’s epic poem, tied to the mast of a similar ship as he resisted the Siren’s calls.

Archaeologist discover the worlds oldest shipwreck in the Black Sea

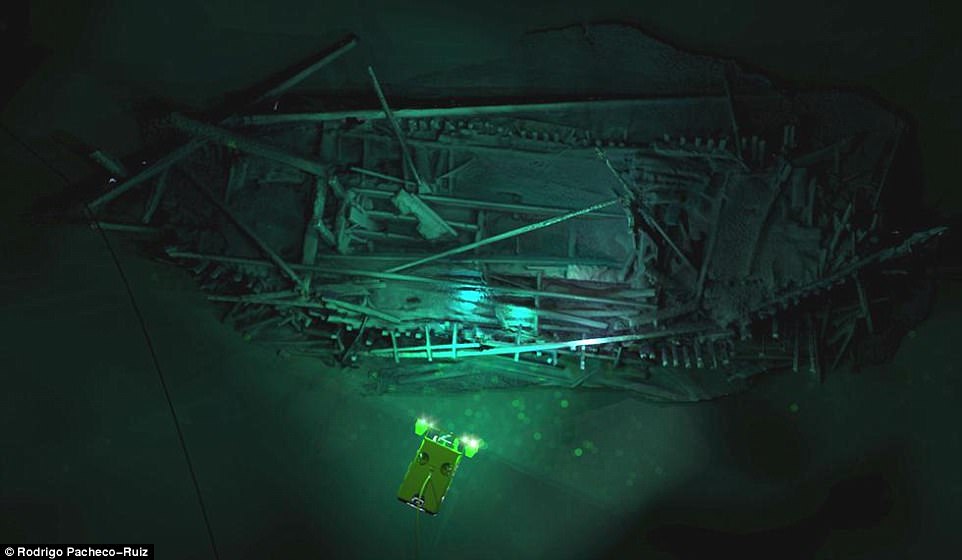

The 75ft shipwreck was been found lying whole with its mast, rudders and rowing benches after more than 2,400 years. The shipwreck was found nearly 7,000ft under the sea in ‘remarkable’ condition, with some suggesting it has similarities to a ship shown on an ancient vase that depicts Odysseus tying the mast of a similar ship as he resisted the Siren’s call. A remote-controlled submarine piloted by British scientists spotted the ship lying on its side about 50 miles off the coast of Bulgaria.

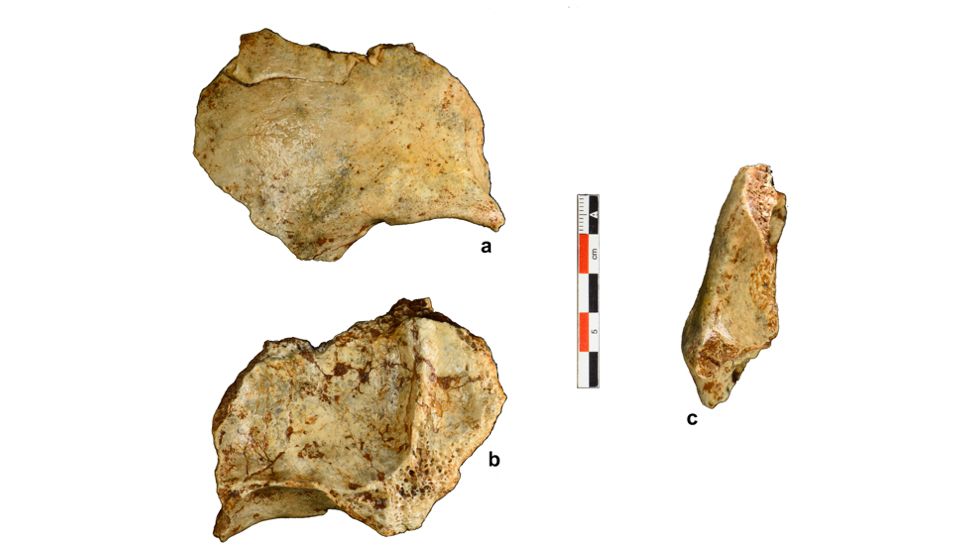

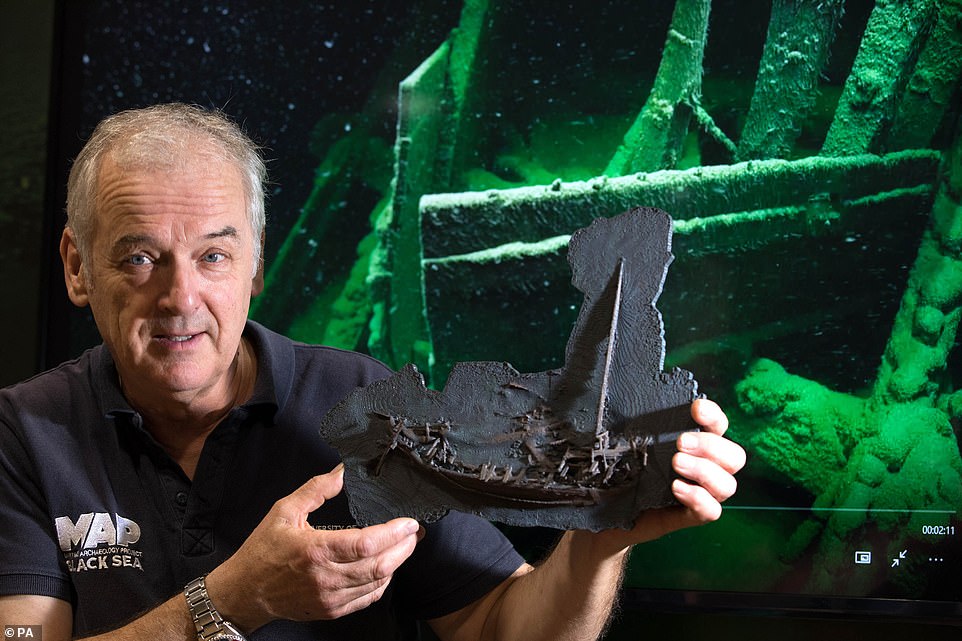

The ship lies in over 1.3miles of water, deep in the Black Sea where the water is anoxic (oxygen free) which can preserve organic material for thousands of years. A small piece of the vessel has been carbon dated and it is confirmed as coming from 400BC – making the ship the oldest intact shipwreck known to mankind. Jon Adams, the project’s chief scientist, said the wreck was very well-preserved, with the rudder and tiller still in place.

‘A ship, surviving intact, from the Classical world, lying in over 2km of water, is something I would never have believed possible,’ he said

‘This will change our understanding of shipbuilding and seafaring in the ancient world.’

Prior to this discovery ancient ships had only been found in fragments with the oldest more than 3,000 years old. The team from the Black Sea Maritime Archaeological Project said the find also revealed how far from the shore ancient Greek traders could travel. Adams told The Times the ship probably sank in a storm, with the crew unable to bail water in time to save it.

The archaeologist believes it probably held 15 to 25 men at the time whose remains may be hidden in the surrounding sediment or eaten by bacteria. He said he plans to leave the ship on the seabed because raising it would be hugely expensive and require taking the pint joints apart.

The ship was both oar and sail-powered. It was chiefly used for trading but the professor believes it may have been involved in ‘a little bit of raiding’ of coastal cities. It was probably based at one of the ancient Greek settlements on what is now the Bulgarian coast.

He said: ‘Ancient seafarers were not hugging the coast timidly going from port to port but going blue-water sailing.’

The find is one of 67 wrecks found in the area. Previous finds were discovered dating back as far as 2,500 years, including galleys from the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires. Scientists stumbled upon the graveyard while using underwater robots to survey the effects of climate change along the Bulgarian coast. Because the Black Sea contains almost no light or oxygen, little life can survive, meaning the wrecks are in excellent condition.

Researchers say their discovery is ‘truly unrivalled’.

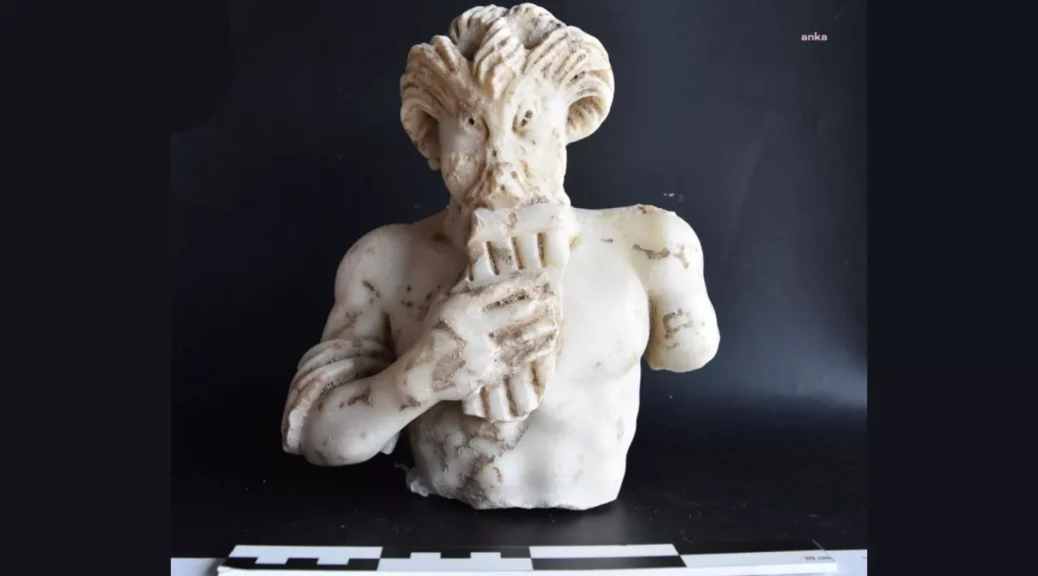

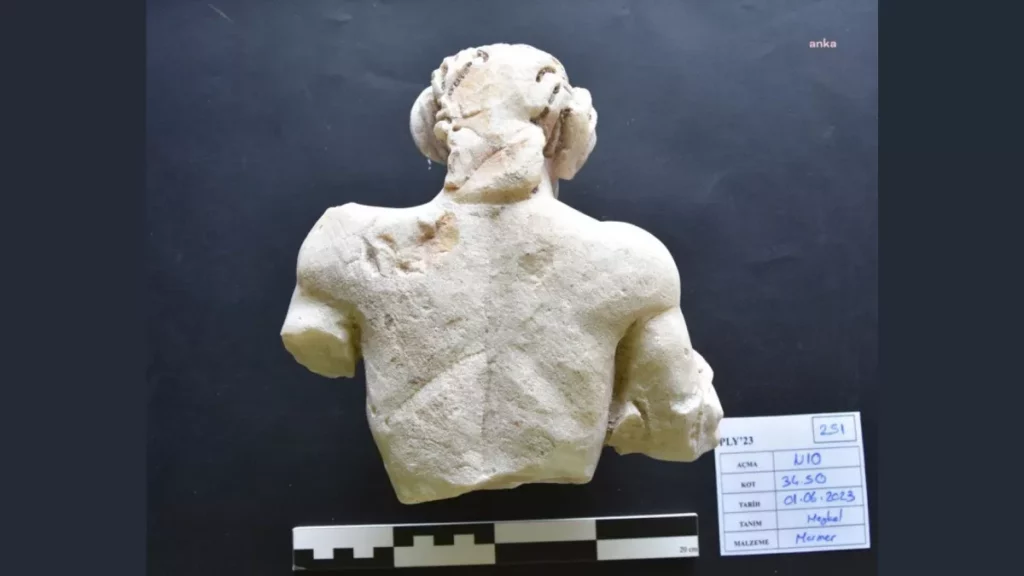

Many of the ships have features that are only known from drawings or written description but never seen until now. Carvings in the wood of some ships have remained intact for centuries, while well-preserved rope was found aboard one 2,000-year-old Roman vessel. The project, known Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project (Black Sea MAP), involves an international team led by the University of Southampton’s Centre for Maritime Archaeology. Ed Parker, CEO of Black Sea MAP, said: ‘Some of the ships we discovered had only been seen on murals and mosaics until this moment.

‘There’s one medieval trading vessel where the towers on the bow and stern are pretty much still there.

‘It’s as if you are looking at a ship in a movie, with ropes still on the deck and carvings in the wood.

‘When I saw that ship, the excitement really started to mount – what we have found is truly unrivalled.’

Most of the vessels found are around 1,300 years old, but the oldest dates back to the 4th Century BC. Many of the wrecks’ details and locations are being kept secret by the team to ensure they remain undisturbed. Black Sea water below 150 metres (490 ft) is anoxic, meaning the environment cannot support the organisms that typically feast on organic materials, such as wood and flesh.

As a result, there is an extraordinary opportunity for preservation, including shipwrecks and the cargoes they carried. Ships lie hundreds or thousands of metres deep with their masts still standing, rudders in place, cargoes of amphorae and ship’s fittings lying on deck. Many of the ships show structural features, fittings and equipment that are only known from drawings or written description but never seen until now.

Project leader Professor Jon Adams, of the University of Southampton, said: ‘This assemblage must comprise one of the finest underwater museums of ships and seafaring in the world.’

The expedition has been scouring the waters 1,800 metres (5,900ft) below the surface of the Black Sea since 2015 using an off-shore vessel equipped with some of the most advanced underwater equipment in the world. The vessel is on an expedition mapping submerged ancient landscapes which were inundated with water following the last Ice Age.

The researchers had discovered over 40 wrecks across two previous expeditions, but during their latest trip, which spanned several weeks and returned this month, they uncovered more than 20 new sites.

Returning to the Port of Burgas in Bulgaria, Professor Jon Adams said: ‘Black Sea MAP now draws towards the end of its third season, acquiring more than 1300km [800 miles] of survey so far, recovering another 100m (330 ft) of sediment core samples and discovering over 20 new wreck sites, some dating to the Byzantine, Roman and Hellenistic periods.’

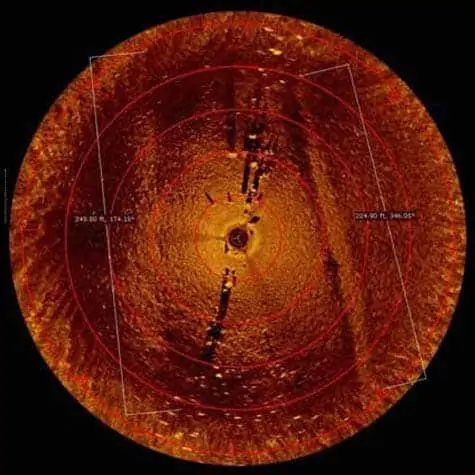

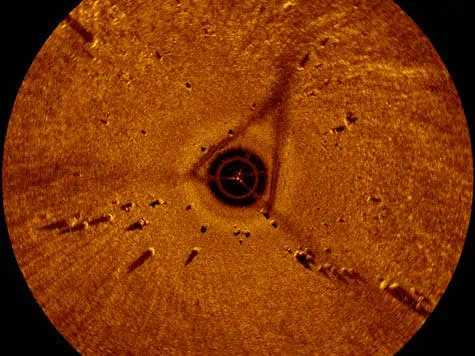

The researchers are using two Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) to survey the sea bed. One is optimised for high resolution 3D photography, while the other, called Surveyor Interceptor, ‘flies’ at four times the speed of conventional ROVs. The Interceptor carries an entire suite of geophysical instrumentation, as well as lights, high definition cameras and a laser scanner. Since the project started, Surveyor Interceptor has set new records for depth at 5,900ft (1,800 metres) and sustained speed of over six knots (7mph), and has covered 1,250 kilometres (776 miles). Among the wrecks are ships from the Roman, Ottoman and Byzantine Empires, which provide new information on the communities on the Black Sea coast.

Many of the colonial and commercial activities of ancient Greece and Rome, and of the Byzantine Empire, centred on the Black Sea. After 1453, when the Ottoman Turks occupied Constantinople – and changed its name to Istanbul – the Black Sea was virtually closed to foreign commerce. Nearly 400 years later, in 1856, the Treaty of Paris re-opened the sea to the commerce of all nations.

The scientists were followed by Bafta-winning filmmakers for much of the three-year project and a documentary is expected in the coming years. Producer Andy Byatt, who worked on the David Attenborough BBC series ‘Blue Planet’, said: ‘I think we have all been blown away by the remarkable finds that Professor Adams and his team have made.

‘The quality of the footage revealing this hidden world is absolutely unique.’