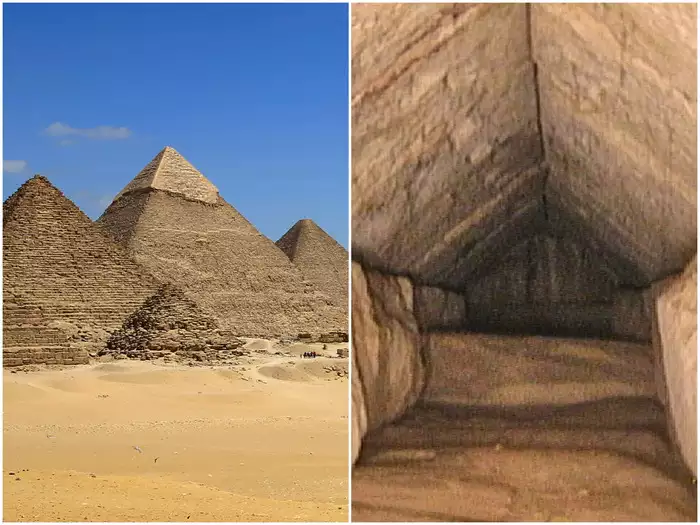

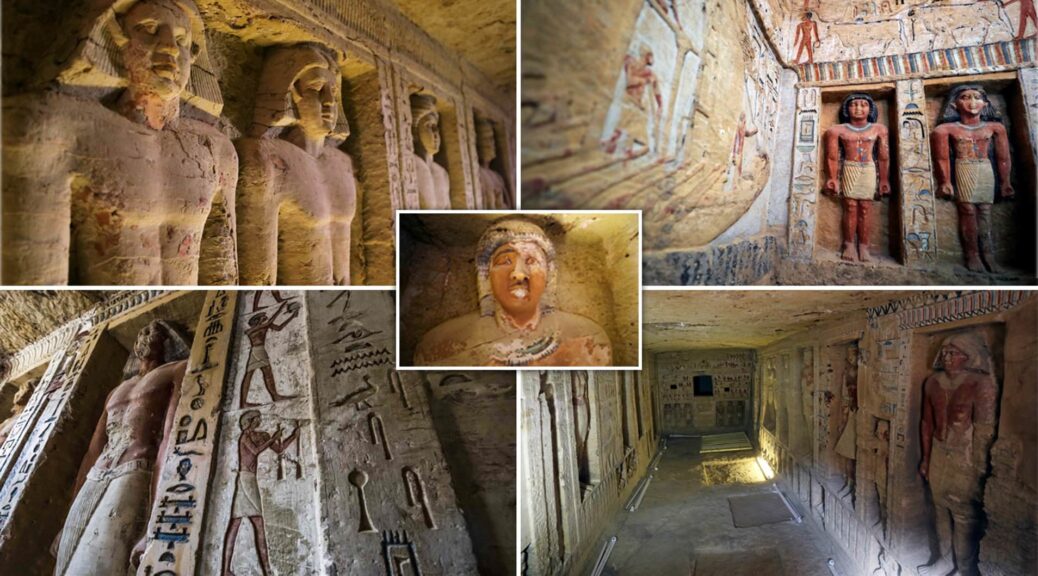

A 30-Foot-Long Hidden Corridor was discovered in the 4,500-year-old Great Pyramid of Giza!

A 30-foot-long hidden corridor was discovered on March 2, 2023, in the Great Pyramid of Giza. This monument is the last standing Ancient Wonder of the World. This North Facing Corridor (NFC) is the first discovery uncovered on the monument’s north side.

The corridor is located above the ancient entrance of the pyramid, behind a chevron-shaped structure that is visible outside the pyramid. This fascinating discovery within the pyramid was made under the ScanPyramids project using muon tomography, a non-invasive technology.

The ScanPyramids Project – An Initiative to Uncover the Hidden Secrets in the Pyramids

The Great Pyramid was constructed around 2560 BCE during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu. The height of the monumental tomb was around 146 meters when it was constructed. But it now stands at 139 meters with much of its limestone casing removed.

The pyramid consists of an elaborate system of passageways and chambers. However, not all of them have been uncovered yet.

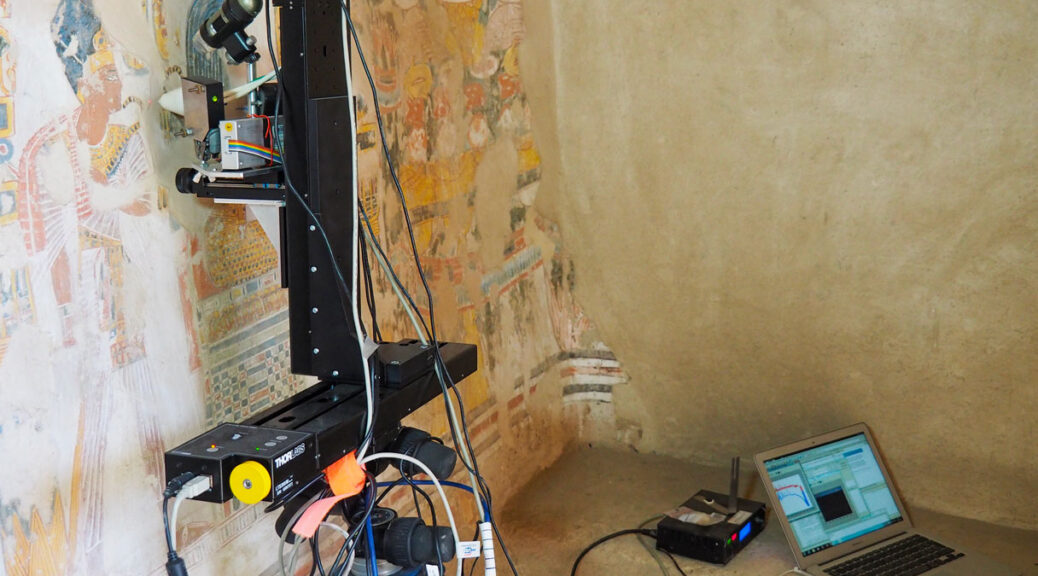

In order to detect the presence of unknown voids and structures without excavating, the ScanPyramids project was launched in 2015. This Egyptian-international project is designed and led by Cairo University and the French HIP Institute (Heritage Innovation Preservation). The project combines several non-invasive and non-destructive techniques, such as 3D simulations, infrared thermography, muon tomography, and other reconstruction techniques, to scan the structure.

The 30-Foot Long Hidden Corridor Was Discovered Using Non-Invasive Technology.

As part of the ScanPyramids project, the most recent discovery is a 30-foot-long hidden corridor in the Great Pyramid of Giza. Egyptian antiquities officials confirmed its discovery on March 2, 2023.

The corridor was detected using muon tomography, a non-invasive technology that uses cosmic ray muons to generate three-dimensional images of objects. In order to retrieve images of what lies within, researchers inserted an endoscope into a tiny joint in the pyramid stones. However, no artifacts were visible in the captured images.

Mostafa Waziri, head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, said that the hidden corridor might have been constructed to redistribute the weight within the massive monument. In fact, in another part of the pyramid, there are five rooms atop the King’s Burial Chamber, which are thought to have been built to redistribute the weight of the massive structure. Waziri also added that they would continue scanning to figure out what is underneath the chamber at the end of the corridor.

Scientists also believe that structural innovations constructed by the Egyptian tomb builders were mostly for pragmatic reasons rather than storing any hidden treasure. For example, the discovered hidden corridor could be related to the construction of the chevron as a first test of the structure before it was used later, higher up in the pyramid. Therefore, there is little likelihood anything major or valuable will be found inside these chambers.

An article published in the Nature Communications journal said that the discovery of this hidden corridor could help in gaining knowledge about the structure and techniques used in the construction of the pyramid. In addition, it could also help in understanding the purpose of the gabled limestone structure that sits in front of the corridor.

Furthermore, Egyptian antiquities officials believe that this amazing discovery could serve as a catalyst for conducting further research in other mysterious inner chambers.

Other Extraordinary Discoveries of the ScanPyramids Project

The ScanPyramids project has led to many other astonishing discoveries in the past. In 2016, researchers discovered a void behind the north face of the Great Pyramid. Following this, in 2017, they discovered a bigger “plane-sized” void, around 98 feet long, above the Grand Gallery.

Thus, we can conclude that even though the tomb commissioned by Pharaoh Khufu has been explored for years together, there are many more mysteries yet to be unraveled.

Scientists plan to continue these non-invasive scans at the Great Pyramid of Giza to uncover more hidden secrets as part of the ScanPyramids project. They also plan to use sophisticated muon detectors to detect the presence of artifacts, if any