Advanced imaging techniques reveal secrets of sealed ancient Egyptian animal coffins

Researchers from the British Museum have gained valuable insight into the contents of six sealed ancient Egyptian animal coffins using cutting-edge neutron tomography.

Lead researcher Daniel O’Flynn and his colleagues present the findings of their examination of six sealed ancient Egyptian animal coffins, all of which were dated between 650 and 250 BC, in a new article published in Scientific Reports.

It is thought that animals were sacrificed and mummified to honor the gods, some serving as offerings or even participating in rituals, while others served as physical manifestations of the gods.

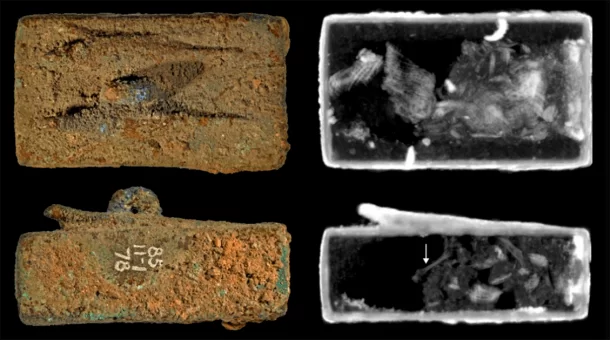

The researchers examined the coffins’ interiors using the non-invasive neutron tomography technique to check for any signs of the animals that had been interred there.

They were able to detect actual biological materials in the coffins, which could be linked to specific animals known to have existed in Egypt during the first millennium BC, much to their delight.

This study’s findings were significant for two reasons. First, the study demonstrated that the animal coffins were just that—coffins—real coffins used to bury actual animals. As had been suspected but previously unprovable, the animal images engraved on the top of the boxes actually did represent the animals sealed inside.

Daniel O’Flynn of the British Museum, who led the study published in Scientific Reports, said: “The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of neutron tomography for the study of mummified remains inside sealed metal containers, providing evidence linking the animal figures on top of votive boxes to the concealed remains.”

The coffins, made of copper compounds, were discovered in various locations, including the ancient cities of Naucratis and Tell El Yehudiyeh. Respectively, the coffins bore figures of lizards, eels, and part-eel, part-cobra creatures with human heads.

The authors note that it is rare for such coffins to still be sealed. Inside the coffins, researchers found intact skulls similar to North African wall lizard species, broken-down bones, and textile fragments believed to be linen.

“Linen was commonly used in ancient Egyptian mummification, and we suspect it was wrapped around the animals before they were placed in the coffins,” explained Dr O’Flynn.

The authors found lead within the three coffins without loops, which they suggest may have been used to aid weight distribution within two of them and to repair a hole found in the other.

They speculate that lead may have been selected due to its status in ancient Egypt as a magical material, as previous research has proposed that lead was used in love charms and curses.

The study also posited that loops found on the exterior of three coffins may have been used to hang them from shrine or temple walls, statues or boats during religious processions, indicating the deep importance animals played in religious practices. While the heavier lead-containing coffins without loops may have been used for different purposes.

Cover Photo: An animal coffin, surmounted by a human-headed part-eel, part-cobra creature wearing a double crown, is one of six sealed ancient Egyptian animal coffins researchers have studied.