Residues in Mesopotamia’s Mass-Produced Pottery Analyzed

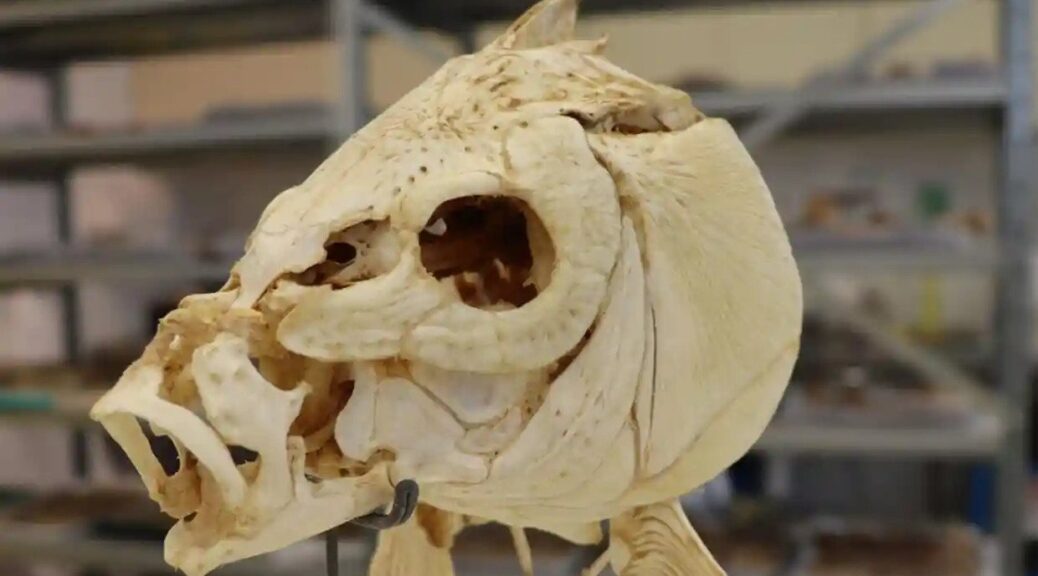

The world’s first urban state societies developed in Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, some 5500 years ago. No other artefact type is more symbolic of this development than the so-called Beveled Rim Bowl (BRB), the first mass-produced ceramic bowl.

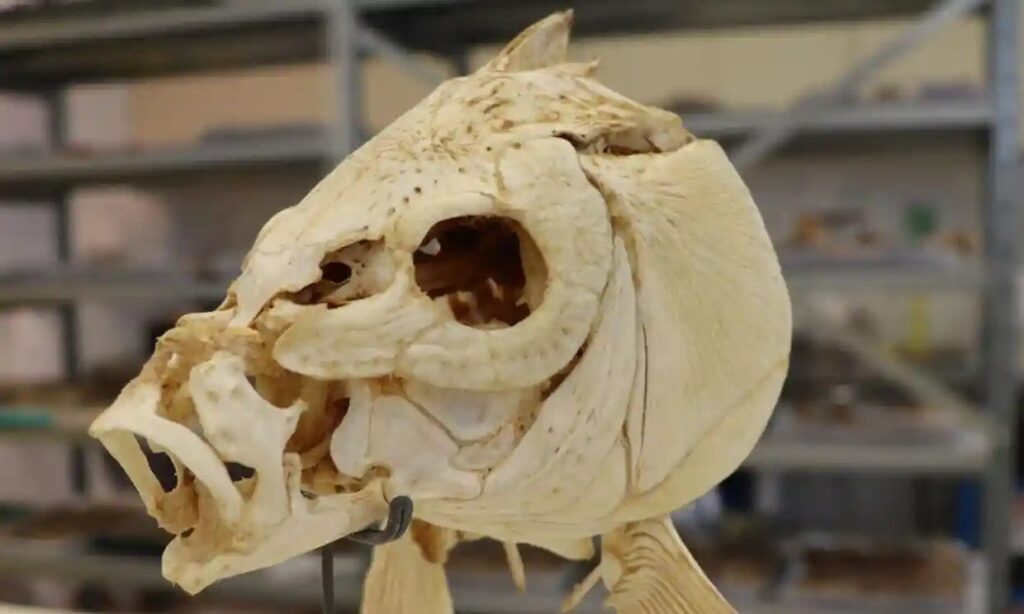

BRB function and what food(s) these bowls contained have been the subject of debate for over a century. A paper published today in The Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports shows that BRBs contained a variety of foods, but especially meat-based meals, most likely bone marrow-flavoured stews or broths.

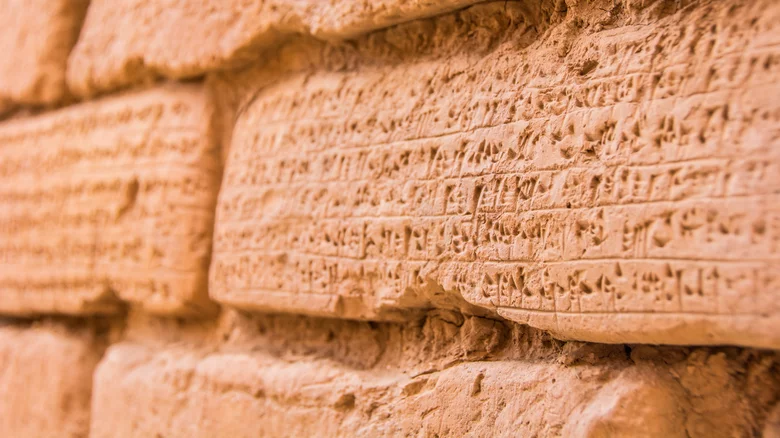

Chemical compounds and stable isotope signatures of animal fats were discovered in BRBs from the Late Chalcolithic site of Shakhi Kora located in the Upper Diyala/Sirwan River Valley of north-eastern Iraq.

An international team led by Professor Claudia Glatz of the University of Glasgow has been carrying out excavations at Shakhi Kora since 2019 as part of the Sirwan Regional Project.

BRBs are mass-produced, thick-walled, conical vessels that appear to spread from southern, lowland sites such as Uruk-Warka across northern Mesopotamia, into the Zagros foothills, and beyond. BRBs are found in their thousands at Late Chalcolithic sites, often associated with monumental structures.

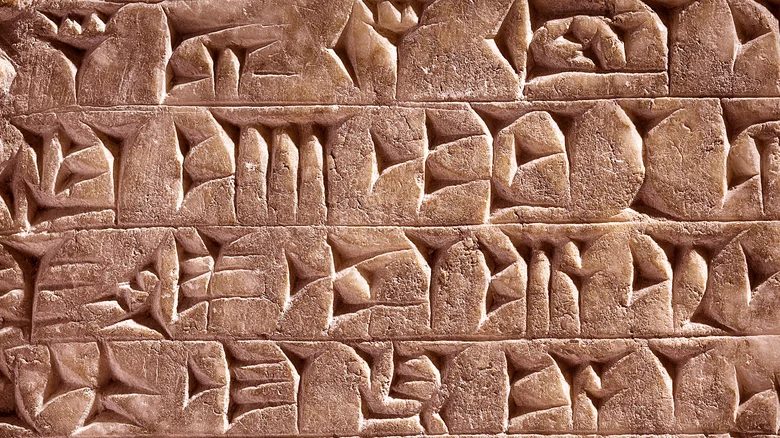

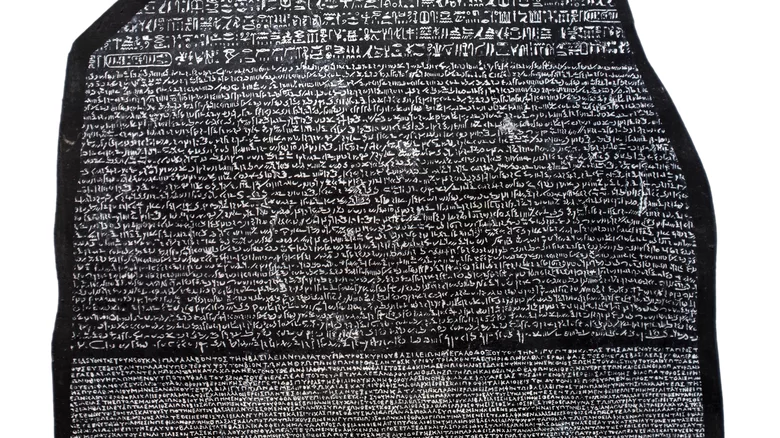

Stylised BRBs appear on the earliest written documents, early cuneiform tablets, and are conventionally interpreted as ration containers used to distribute cereals or cereal-based foods to state-dependent labourers or personnel. Inherently taxable and storable, cereal grains such as wheat, emmer, and barley, have long been considered the economic backbone and main source of wealth and power for early state institutions and their elites.

However, the paper titled “Revealing invisible stews: New results of organic residue analyses of Beveled Rim Bowls from the Late Chalcolithic site of Shakhi Kora, Kurdistan Region of Iraq” states: “Our analytical results challenge traditional interpretations that see BRBs as containers of cereal-based rations and bread moulds. The presence of meat- and potentially also dairy-based foods in the Shakhi Kora vessels lends support to multi-purpose explanations and points to local processes of appropriation of vessel meaning and function.”

Dr Elsa Perruchini, Institut National du Patrimoine, Paris, and University of Glasgow, who carried out the chemical analysis, said: “The combined approach of chemical and isotopic analysis using GC-MS and GC-C-IRMS was employed to identify the source(s) of lipids extracted from ceramic sherds, with the aim of providing new insights into the function of BRBs.”

Professor Claudia Glatz, a Professor of Archaeology at the University of Glasgow and director of the Shakhi Kora excavations, said: “Our results present a significant advance in the study of early urbanism and the emergence of state intuitions.

“They demonstrate that there is significant local variation in the ways in which BRBs were used across Mesopotamia and what foods were served in them, challenging overly state-centric models of early social complexity.

“Our results point towards a great deal of local agency in the adoption and re-interpretation of the function and social symbolism of objects, that are elsewhere unambiguously associated with state institutions and specific practices.

As a result, they open up exciting new avenues of research on the role of food and foodways in the development, negotiation, and possible rejection of the early state at the regional and local level.”

Professor Jaime Toney, Professor of Environmental and Climate Science at the University’s School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, said: “We have been collaborating closely with Claudia and her team for several years to minimise contamination during the collection of vessels from archaeological sites and it is fascinating to see this pay off with the analysis of fossil residues and the stable isotope analysis clearly indicate that they once held animal fats.”