Rock Crystals Recovered from Neolithic Burial Mound in England

Distinctive and rare rock crystals were moved over long distances by Early Neolithic Brits and were used to mark their burial sites, according to groundbreaking new archaeological research.

Evidence for the use of rock crystal – a rare type of perfectly transparent quartz which forms in large hexagonal gems – has occasionally been found at prehistoric sites in the British Isles, but the little investigation has previously been done specifically into how the material was used and its potential significance.

A group of archaeologists from The University of Manchester worked with experts from the University of Cardiff and Herefordshire County Council on a dig at Dorstone Hill in Herefordshire, a mile south of another dig at Arthur’s Stone.

There, they studied a complex of 6000-year-old timber halls, burial mounds and enclosures from the Early Neolithic period, when farming and agriculture arrived in Britain for the first time.

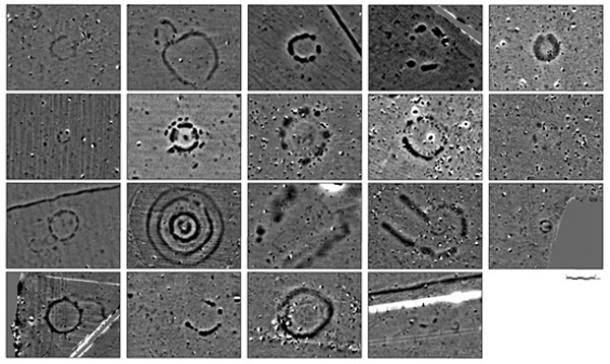

As well as a range of artefacts including pottery, stone implements and cremated bones, they uncovered rock crystal which had been knapped like the flint at the site, but unlike the flint, it had not been turned into tools such as arrowheads or scrapers – instead, pieces were intentionally gathered and deposited within the burial mounds.

The experts say the material was deposited at the site over many generations, potentially for up to 300 years.

Only a few places in the British Isles have produced pure crystals large enough to produce the material at Dorstone Hill, the closest being Snowdonia in North Wales and St David’s Head in South West Wales – this means that the ancient Brits must have carried the material across large distances to reach the site.

As a result, the researchers speculate that the material may have been used by people to demonstrate their local identities and their connections with other places around the British Isles.

“It was highly exciting to find the crystal because it is exceptionally rare – in a time before the glass, these pieces of perfectly transparent solid material must have been really distinctive,” said lead researcher Nick Overton.

“I was very interested to discover where the material came from, and how people might have worked and used it.”

“The crystals would have looked very unusual in comparison to other stones they used, and are extremely distinctive as they emit light when hit or rubbed together and produce small patches of rainbow – we argue that their use would have created memorable moments that brought individuals together, forged local identities and connected the living with the dead whose remains they were deposited with.„

The researchers plan to study materials found at other sites to discover whether people were working with this material in similar ways, in order to uncover connections and local traditions.

They also intend to look at the chemical composition of the crystal to find out if they can track down its specific source.