An archaeologist says he’s discovered the world’s oldest pyramids 7,400 Years older than Egyptian pyramids

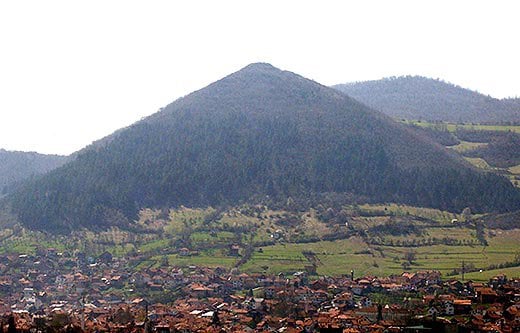

Sam Osmanagich kneels down next to a low wall, part of a 6-by-10-foot rectangle of fieldstone with an earthen floor. If I’d come upon it in a farmer’s backyard here on the edge of Visoko—in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 15 miles northwest of Sarajevo—I would have assumed it to be the foundation of a shed or cottage abandoned by some 19th-century peasant. Osmanagich, a blond, 49-year-old Bosnian who has lived for 16 years in Houston, Texas, has a more colorful explanation. “Maybe it’s a burial site, and maybe it’s an entrance, but I think it’s some type of ornament, because this is where the western and northern sides meet,” he says, gesturing toward the summit of Pljesevica Hill, 350 feet above us. “You find evidence of the stone structure everywhere. Consequently, you can conclude that the whole thing is a pyramid.”

Not just any pyramid, but what Osmanagich calls the Pyramid of the Moon, the world’s largest—and oldest—step pyramid. Looming above the opposite side of town is the so-called Pyramid of the Sun—also known as Visocica Hill—which, at 720 feet, also dwarfs the Great Pyramids of Egypt. A third pyramid, he says, is in the nearby hills. All of them, he says, are some 12,000 years old. During that time much of Europe was under a mile-thick sheet of ice and most of humanity had yet to invent agriculture. As a group, Osmanagich says, these structures are part of “the greatest pyramidal complex ever built on the face of the earth.”

In a country still recovering from the 1992-95 genocidal war, in which some 100,000 people were killed and 2.2 million were driven from their homes (the majority of them Bosnian Muslims), Osmanagich’s claims have found a surprisingly receptive audience. Even Bosnian officials—including a prime minister and two presidents—have embraced them, along with the Sarajevo-based news media and hundreds of thousands of ordinary Bosnians, drawn to the promise of a glorious past and a more prosperous future for their battered country. Skeptics, who say the pyramid claims are examples of pseudo-archaeology pressed into the service of nationalism, have been shouted down and called anti-Bosnian. Pyramid mania has descended upon Bosnia. Over 400,000 people have visited the sites since October 2005, when Osmanagich announced his discovery. Souvenir stands peddle pyramid-themed T-shirts, wood carvings, piggy banks, clocks and flip-flops. Nearby eateries serve meals on pyramid-shaped plates and coffee comes with pyramid-emblazoned sugar packets. Foreigners by the thousands have come to see what all the fuss is about, drawn by reports by the BBC, Associated Press, Agence France-Presse and ABC’s Nightline (which reported that thermal imaging had “apparently” revealed the presence of man-made, concrete blocks beneath the valley).

Osmanagich has also received official backing. His Pyramid of the Sun Foundation in Sarajevo has garnered hundreds of thousands of dollars in public donations and thousands more from state-owned companies. After Malaysia’s former prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, toured Visoko in July 2006, more contributions poured in. Christian Schwarz-Schilling, the former high representative for the international community in Bosnia and Herzegovina, visited the site in July 2007, then declared that “I was surprised with what I saw before my eyes, and the fact that such structures exist in Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

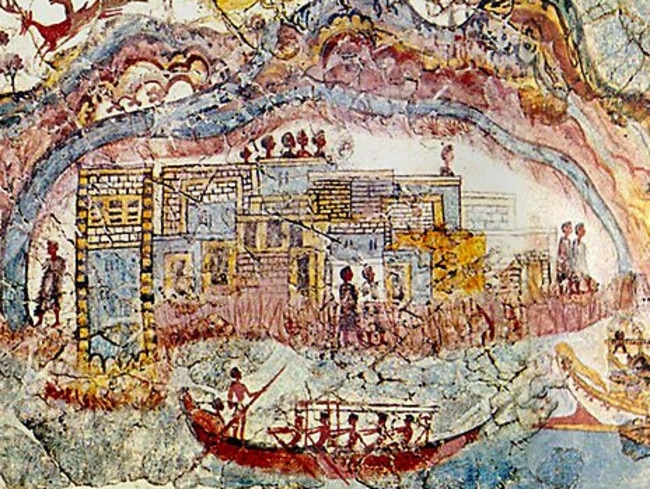

Osmanagich’s many appearances on television have made him a national celebrity. In Sarajevo, people gape at him on the streets and seek his autograph in cafés. When I was with him one day at the entrance to city hall, guards jumped out of their booths to embrace him. Five years ago, almost no one had ever heard of him. Born in Zenica, about 20 miles north of Visoko, he earned a master’s degree in international economics and politics at the University of Sarajevo. (Years later, he obtained a doctorate in the sociology of history. ) He left Bosnia before its civil war, emigrating to Houston in 1993 (because, in part, of its warm climate), where he started a successful metalworking business that he still owns today. While in Texas he got interested in the Aztec, Incan and Maya civilizations and made frequent trips to visit pyramid sites in Central and South America. He says that he’s visited hundreds of pyramids worldwide.

His views of world history—described in his books published in Bosnia—are unconventional. In The World of the Maya, which was reprinted in English in the United States, he writes that “Mayan hieroglyphics tell us that their ancestors came from the Pleiades….first arriving at Atlantis where they created an advanced civilization.” He speculates that when a 26,000-year cycle of the Maya calendar is completed in 2012, humankind might be raised to a higher level by vibrations that will “overcome the age of darkness which has been oppressing us.” In another work, Alternative History, he argues that Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders escaped to a secret underground base in Antarctica from which they did battle with Adm. Richard Byrd’s 1946 Antarctic expedition.

“His books are filled with these kinds of stories,” says journalist Vuk Bacanovic, one of Osmanagich’s few identifiable critics in the Sarajevo press corps. “It’s like a religion based on corrupted New Age ideology.”

In April 2005, while in Bosnia to promote his books, Osmanagich accepted an invitation to visit a local museum and the summit of Visocica, which is topped by the ruins of Visoki, a seat of Bosnia’s medieval kings. “What really caught my eye was that the hill had the shape of a pyramid,” he recalls. “Then I looked across the valley and I saw what we today call the Bosnian Pyramid of the Moon, with three triangular sides and a flat top.” Upon consulting a compass, he concluded the sides of the pyramid were perfectly oriented toward the cardinal points (north, south, east and west). He was convinced this was not “the work of Mother Nature.”

After his mountaintop epiphany, Osmanagich secured digging permits from the appropriate authorities, drilled some core samples and wrote a new book, The Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun, which announced “to the world that in the heart of Bosnia” is a hidden “stepped pyramid whose creators were ancient Europeans.” He then set up a nonprofit foundation called the Archaeological Park: Bosnian Pyramid of the Sun Foundation, which allowed him to seek funding for his planned excavation and preservation work.

“When I first read about the pyramids I thought it was a very funny joke,” says Amar Karapus, a curator at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo. “I just couldn’t believe that anyone in the world could believe this.”

Visoko lies near the southern end of a valley that runs from Sarajevo to Zenica. The valley has been quarried for centuries and its geological history is well understood. It was formed some ten million years ago as the mountains of Central Bosnia were pushing skyward and was soon flooded, forming a lake 40 miles long. As the mountains continued to rise over the next few million years, sediments washed into the lake and settled on the bottom in layers. If you dig in the valley today, you can expect to find alternating layers of various thickness, from gossamer-thin clay sediments (deposited in quiet times) to plates of sandstones or thick layers of conglomerates (sedimentary rocks deposited when raging rivers dumped heavy debris into the lake). Subsequent tectonic activity buckled sections of lakebed, creating angular hills, and shattered rock layers, leaving fractured plates of sandstone and chunky blocks of conglomerate. In early 2006 Osmanagich asked a team of geologists from the nearby University of Tuzla to analyze core samples at Visocica. They found that his pyramid was composed of the same matter as other mountains in the area: alternating layers of conglomerate, clay and sandstone.

Nonetheless, Osmanagich put scores of laborers to work digging on the hills. It was just as the geologists had predicted: the excavations revealed layers of fractured conglomerate at Visocica, while those at Pljesevica uncovered cracked sandstone plates separated by layers of silt and clay. “What he’s found isn’t even unusual or spectacular from the geological point of view,” says geologist Robert Schoch of Boston University, who spent ten days at Visoko that summer. “It’s completely straightforward and mundane.”

“The landform [Osmanagich] is calling a pyramid is actually quite common,” agrees Paul Heinrich, an archaeological geologist at Louisiana State University. “They’re called ‘flatirons’ in the United States and you see a lot of them out West.” He adds that there are “hundreds around the world,” including the “Russian Twin Pyramids” in Vladivostok.

Apparently unperturbed by the University of Tuzla report, Osmanagich said Visocica’s conglomerate blocks were made of concrete that ancient builders had poured on-site. This theory was endorsed by Joseph Davidovits, a French materials scientist who, in 1982, advanced another controversial hypothesis—that the blocks making up the Egyptian pyramids were not carved, as nearly all experts believe, but cast in limestone concrete. Osmanagich dubbed Pljesevica’s sandstone plates “paved terraces,” and according to Schoch, workers carved the hillside between the layers—to create the impression of stepped sides on the Pyramid of the Moon. Particularly uniform blocks and tile sections were exposed for viewing by dignitaries, journalists and the many tourists who descended on the town.

Osmanagich’s announcements sparked a media sensation, stoked with a steady supply of fresh observations: a 12,000-year-old “burial mound” (without any skeletons) in a nearby village; a stone on Visocica with alleged curative powers; a third pyramid dubbed the Pyramid of the Dragon; and two “shaped hills” that he has named the Pyramid of Love and the Temple of Earth. And Osmanagich has recruited an assortment of experts whom he says vindicate his claims. For instance, in 2007, Enver Buza, a surveyor from Sarajevo’s Geodetic Institute, published a paper stating that the Pyramid of the Sun is “oriented to the north with a perfect precision.”

Many Bosnians have embraced Osmanagich’s theories, particularly those from among the country’s ethnic Bosniaks (or Bosnian Muslims), who constitute about 48 percent of Bosnia’s population. Visoko was held by Bosniak-led forces during the 1990s war, when it was choked with refugees driven out of surrounding villages by Bosnian Serb (and later, Croat) forces, who repeatedly shelled the town. Today it is a bastion of support for the Bosniaks’ nationalist party, which controls the mayor’s office. A central tenet of Bosniak national mythology is that Bosniaks are descended from Bosnia’s medieval nobility. Ruins of the 14th-century Visoki Castle can be found on the summit of Visocica Hill—on top of the Pyramid of the Sun—and, in combination, the two icons create considerable symbolic resonance for Bosniaks. The belief that Visoko was a cradle of European civilization and that the Bosniaks’ ancestors were master builders who surpassed even the ancient Egyptians has become a matter of ethnic pride. “The pyramids have been turned into a place of Bosniak identification,” says historian Dubravko Lovrenovic of the Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission to Preserve National Monuments. “If you are not for the pyramids, you are accused of being an enemy of the Bosniaks.”

For his part, Osmanagich insists he disapproves of those who exploit his archaeological work for political gain. “Those pyramids don’t belong to any particular nationality,” he says. “These are not Bosniak or Muslim or Serb or Croat pyramids, because they were built at a time when those nations and religions were not in existence.” He says his project should “unite people, not divide them.”

Yet Bosnia and Herzegovina still bears the deep scars of a war in which the country’s Serbs and, later, Croats sought to create ethnically pure small states by killing or expelling people of other ethnicities. The most brutal incident occurred in 1995, when Serb forces seized control of the town of Srebrenica—a United Nations-protected “safe haven”—and executed some 8,000 Bosniak men of military age. It was the worst civilian massacre in Europe since World War II.

Wellesley College anthropologist Philip Kohl, who has studied the political uses of archaeology, says that Osmanagich’s pyramids exemplify a narrative common to the former Eastern bloc. “When the Iron Curtain collapsed, all these land and territorial claims came up, and people had just lost their ideological moorings,” he notes. “There’s a great attraction in being able to say, ‘We have great ancestors, we go back millennia and we can claim these special places for ourselves.’ In some places it’s relatively benign; in others it can be malignant.”

“I think the pyramids are symptomatic of a traumatized society that is still trying to recover from a truly horrendous experience,” says Andras Riedlmayer, a Balkan specialist at Harvard University. “You have many people desperate for self-affirmation and in need of money.”

Archaeological claims have long been used to serve political purposes. In 1912, British archaeologists combined a modern skull with an orangutan jaw to fabricate a “missing link” in support of the claim that human beings arose in Britain, not Africa. (The paleontologist Richard Leakey later noted that English elites took so much pride in “being the first, that they swallowed [the hoax] hook, line and sinker.” )

More recently, in 2000, Shinichi Fujimura—a prominent archaeologist whose finds suggested that Japanese civilization was 700,000 years old—was revealed to have buried the forged artifacts he had supposedly discovered. “Fujimura’s straightforward con was undoubtedly accepted by the establishment, as well as the popular press, because it gave them evidence of what they already wanted to believe—the great antiquity of the Japanese people,” Michele Miller wrote in the archaeological journal Athena Review.

Some Bosnian scholars have publicly opposed Osmanagich’s project. In April 2006, twenty-one historians, geologists and archaeologists signed a letter published in several Bosnian newspapers describing the excavations as amateurish and lacking proper scientific supervision. Some went on local television to debate Osmanagich. Bosniak nationalists retaliated, denouncing pyramid opponents as “corrupt” and harassing them with e-mails. Zilka Kujundzic-Vejzagic of the National Museum, one of the Balkans’ pre-eminent archaeologists, says she received threatening phone calls. “One time I was getting onto the tram and a man pushed me off and said, ‘You’re an enemy of Bosnia, you don’t ride on this tram,'” she recalls. “I felt a bit endangered.”

“I have colleagues who have gone into silence because the attacks are constant and very terrible,” says University of Sarajevo historian Salmedin Mesihovic. “Every day you feel the pressure.”

“Anyone who puts their head above the parapet suffers the same fate,” says Anthony Harding, a pyramid skeptic who was, until recently, president of the European Association of Archaeologists. Sitting in his office at the University of Exeter in England, he reads from a thick folder of letters denouncing him as a fool and a friend of the Serbs. He labeled the file “Bosnia—Abuse.”

In June 2006, Sulejman Tihic, then chairman of Bosnia’s three-member presidency, endorsed the foundation’s work. “One does not need to be a big expert to see that those are the remains of three pyramids,” he told journalists at a summit of Balkan presidents. Tihic invited Koichiro Matsuura, then director-general of Unesco, to send experts to determine if the pyramids qualified as a World Heritage site. Foreign scholars, including Harding, rallied to block the move: 25 of them, representing six countries, signed an open letter to Matsuura warning that “Osmanagich is conducting a pseudo-archaeological project that, disgracefully, threatens to destroy parts of Bosnia’s real heritage.”

But the Pyramid Foundation’s political clout appears considerable. When the minister of culture of the Bosniak-Croat Federation, Gavrilo Grahovac, blocked the renewal of foundation permits in 2007—on the grounds that the credibility of those working on the project was “unreliable”—the action was overruled by Nedzad Brankovic, then the federation prime minister. “Why should we disown something that the entire world is interested in?” Brankovic told reporters at a press conference following a visit to the site. “The government will not act negatively toward this project.” Haris Silajdzic, another member of the national presidency, has also expressed support for Osmanagich’s project, on grounds that it helps the economy.

Critics contend that the project not only sullies Bosnian science but also soaks up scarce resources. Osmanagich says his foundation has received over $1 million, including $220,000 from Malaysian tycoon Vincent Tan; $240,000 from the town of Visoko; $40,000 from the federal government; and $350,000 out of Osmanagich’s pocket. Meanwhile, the National Museum in Sarajevo has struggled to find sufficient funds to repair wartime damage and safeguard its collection, which includes more than two million archaeological artifacts and hundreds of thousands of books.

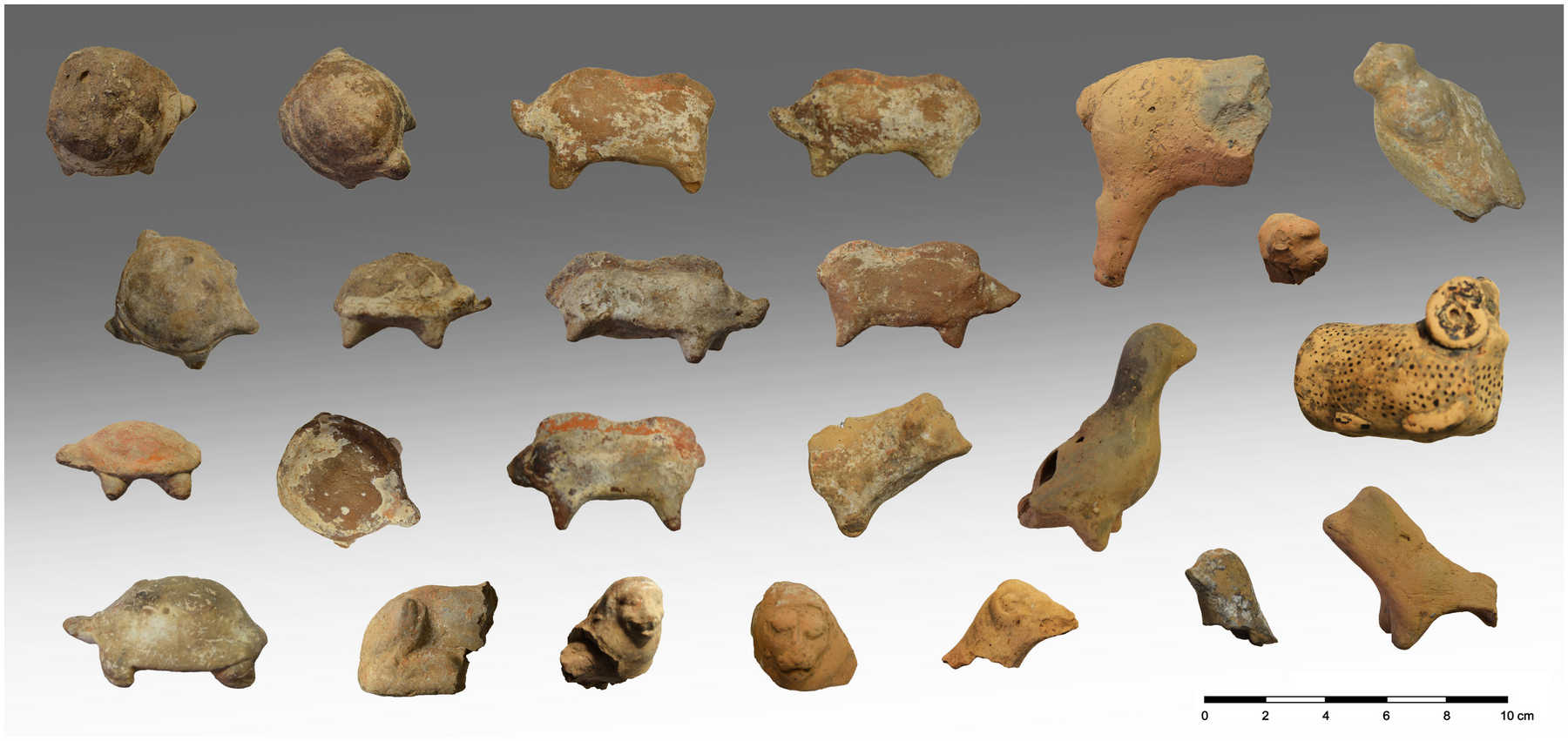

Critics also cite the potential damage to Bosnia’s archae- ological heritage. “In Bosnia, you can’t dig in your back garden without finding artifacts,” says Adnan Kaljanac, a graduate student of ancient history at the University of Sarajevo. Although Osmanagich’s excavation has kept its distance from the medieval ruins on Visocica Hill, Kaljanac worries that the project may destroy undocumented Neolithic, Roman or medieval sites in the valley. Similarly, in a 2006 letter to Science magazine, Schoch said the hills in Visoko “could well yield scientifically valuable terrestrial vertebrate specimens. Presently, the fossils are being ignored and destroyed during the ‘excavations,’ as crews work to shape the natural hills into crude semblances of the Mayan-style step pyramids with which Osmanagich is so enamored.”

That same year, the Commission to Preserve National Monuments, an independent body created in 1995 by the Dayton peace treaty to safeguard historical artifacts from nationalist infighting, asked to inspect artifacts reportedly found at Osmanagich’s site. According to commission head Lovrenovic, commission members were refused access. The commission then expanded the protected zone around Visoki, effectively pushing Osmanagich off the mountain. Bosnia’s president, ministers and parliament currently have no authority to override the commission’s decisions. But if Osmanagich has begun to encounter obstacles in his homeland, he’s had continuing success abroad. This past June, he was made a foreign member of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences, one of whose academicians served as “scientific chairman” of the First International Scientific Conference of the Valley of the Pyramids, which Osmanagich convened in Sarajevo in August 2008. Conference organizers included the Russian Academy of Technical Sciences, Ain Shams University in Cairo and the Archaeological Society of Alexandria. This past July, officials in the village of Boljevac, Serbia, claimed that a team sent by Osmanagich had confirmed a pyramid under Rtanj, a local mountain. Osmanagich e-mailed me he had not visited Rtanj himself nor had he initiated any research at the site. However, he told the Serbian newspaper Danas that he endorsed future study. “This is not the only location in Serbia, nor the region, where there is a possibility of pyramidal structures,” he was quoted as saying.

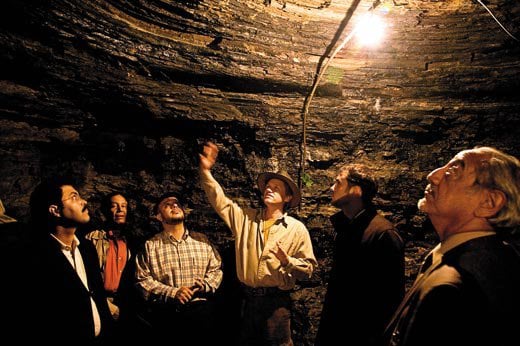

For now Osmanagich has gone underground, literally, to excavate a series of what he says are ancient tunnels in Visoko—which he believes are part of a network that connects the three pyramids. He leads me through one of them, a cramped, three-foot-high passage through disconcertedly unconsolidated sand and pebbles he says he is widening into a seven-foot-tall thoroughfare—the tunnel’s original height, he maintains—for tourists. (The tunnel was partially filled, he says, when sea levels rose by 1,500 feet at the end of the ice age.) He points out various boulders he says were transported to the site 15,000 years ago, some of which bear carvings he says date back to that time. In an interview with the Bosnian weekly magazine BH Dani, Nadija Nukic, a geologist whom Osmanagich once employed, claimed there was no writing on the boulders when she first saw them. Later, she saw what appeared to her as freshly cut marks. She added that one of the foundation’s workers told her he had carved the first letters of his and his children’s names. (After the interview was published, Osmanagich posted a denial from the worker on his Web site. Efforts to reach Nukic have been unavailing.)

Some 200 yards in, we reach the end of the excavated portion of the tunnel. Ahead lies a tenuous-looking crawl space through the gravelly, unconsolidated earth. Osmanagich says he plans to dig all the way to Visocica Hill, 1.4 miles away, adding that, with additional donations, he could reach it in as few as three years. “Ten years from now nobody will remember my critics,” he says as we start back toward the light, “and a million people will come to see what we have.