Possible Medieval Shipwreck Spotted in Norway Lake

“Mjøsa is like a mini-ocean, or a really large fjord,” says marine archaeologist Øyvind Ødegård from NTNU. For centuries, ships and boats have travelled these waters. Diving archaeologists have registered around 20 wrecks in shallow water. But the lake has never been examined beyond scuba diving depth of around 20-30 metres.

“We believed that the chance of finding a shipwreck was quite high, and sure enough, a ship turned up,” Ødegård says.

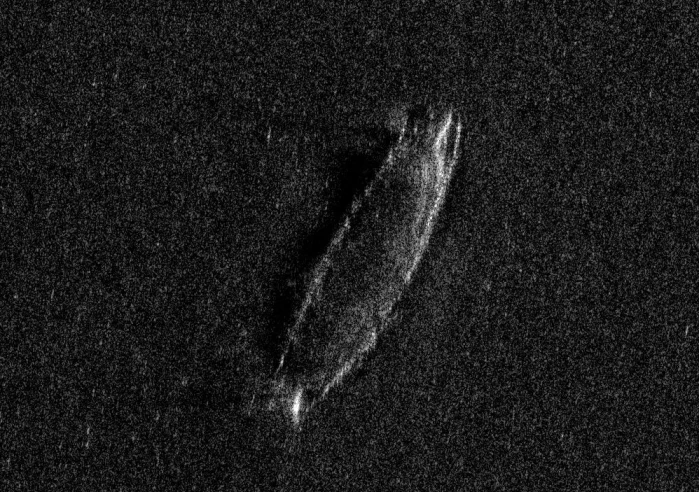

The mapping of the sea bottom of Mjøsa started a couple of weeks ago. It yielded results on the very last day. At 410 metres, the autonomous underwater vehicle Hugin from the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment found a shipwreck.

Possibly a medieval shipwreck

The ship is about ten metres long – it’s possible that it originally was a bit longer – and 2,5 metres wide. This places it somewhere in between the categories of a large boat or a ship, according to Ødegård.

At one end, it looks as though the strakes are no longer fastened properly to the ship, which indicates that the iron nails fastening them have probably begun to rust and disintegrate.

“This tells us that the ship has probably been at the bottom of Mjøsa for a while,” Ødegård says.

The Norwegian newspaper VG excitedly announced for a brief time that the archaeologists had discovered a Viking ship, but this is not the case.

Ødegård explains that Viking ships usually have the steering oar on the side of the ship. During the Middle Ages, the steering oar was rather placed right at the back of the ship – and judging by the images obtained, this is what the shipwreck in question has.

“If this is correct, it is highly likely that the ship is not older than from the 1300s,” Ødegård says.

The ship is clinker built, a Nordic tradition of ship building also known from the Viking ships and listed on the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

“This tradition is recognized as a very important part of our cultural heritage,” says Ødegård.

Naval battles and trade routes

The Norwegian Defence Research Establishment was given the task of mapping Mjøsa by The Norwegian Environment Agency. The job was to find possible explosives and ammunition that may have been dumped in the lake by an ammunition factory which is said to have done so between the 1940s and up until the 70s. Researchers from NTNU had simultaneously started up a project about Mjøsa, and so a collaboration came about.

“We realized that the entire lake is more or less unknown territory,” says Ødegård.

NTNU has therefore started up a research project about Mjøsa starting next year, which will go on for about five years.

Vice principle for NTNU, in Gjøvik, Gro Dæhlin, says to the newspaper VG that Mjøsa is a treasure trove for old ships.

Director of Mjøsmuseet, Arne Julsrud Berg, is also very excited about the find.

He tells VG that there were huge naval battles on Mjøsa in the 1100s and 1200s, when large fleets including ships the size of the famous Gokstad Viking ship met in battle on the water.

“Even during the Viking Age there were huge sea battles on Mjøsa,” Berg says to VG.

The areas surrounding Mjøsa were wealthy farm areas, and goods have been transported across Mjøsa to and from Oslo throughout the centuries.

More to come

Raising the ship would probably pose a very complex task.

“I don’t know if that has ever been done with robots,” says Ødegård.

On Thursday evening this week, having discovered the shipwreck in the sonar images from FFI, Ødegård and the team went out to try and get better images with a different robot, but the waters were too rough.

“What we want to do now is to get data from cameras and other sensors. We can blow away some sand from sediments with the propels on the robot, and we can use manipulator arms, but it will be what we call a non-intrusive investigation at first,” says Ødegård.

The two-week mapping only covered around 40 square kilometres of the 360 sqare kilometre large lake. More ships may turn up – within the next few days, when the researchers analyse more of the data collected, or sometime during next spring, when the next field trip will take place.

“Because this is a freshwater lake, the wood in such a ship is preserved. The metal may rust, and the ship may lose its structure, but the wood is intact. A similar ship to the one we now found, would not have survived for more than a few decades if it had gone down on the coast,” Ødegård says.

“So if we are going to find a Viking shipwreck in Norway, then Mjøsa is probably the place with the most potential for such a find,” he says.