Dyed Cotton Fibers Found at Neolithic Village Site in Israel

Around 7,000 years ago, somebody arrived in a prehistoric village in today’s northern Israel with a luxurious novelty: cotton.

Cotton was not known to the earliest civilizations rising in the Near East because it isn’t indigenous to the region, and where and when it was first domesticated remains a mystery. But now traces of this alien plant with its exquisitely soft bolls have been detected in Tel Tsaf.

This is the earliest trace of cotton found in the Near East to date by centuries, the researchers say. They believe it originated in the Indus Valley, though do not rule out an African origin.

How did cotton get to Tel Tsaf 7,000 years ago from the Indus Valley (or North Africa)? By trading, suggest Li Liu of Stanford University, Maureece Levin of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Florian Klimscha of the Lower Saxony State Museum (Hannover, Germany) and Danny Rosenberg of the University of Haifa, writing in Frontiers in Plant Science.

Good times in the Late Neolithic

Tel Tsaf contains the ruins of a village that arose about 7,300 to 7,200 years ago and would thrive for about 500 years, after which it was deserted for reasons that remain unknown. That in itself is quite the mystery given the abundance of its environs in the central Jordan Valley, south of the Sea of Galilee, Rosenberg notes. But for its time, this had been some settlement.

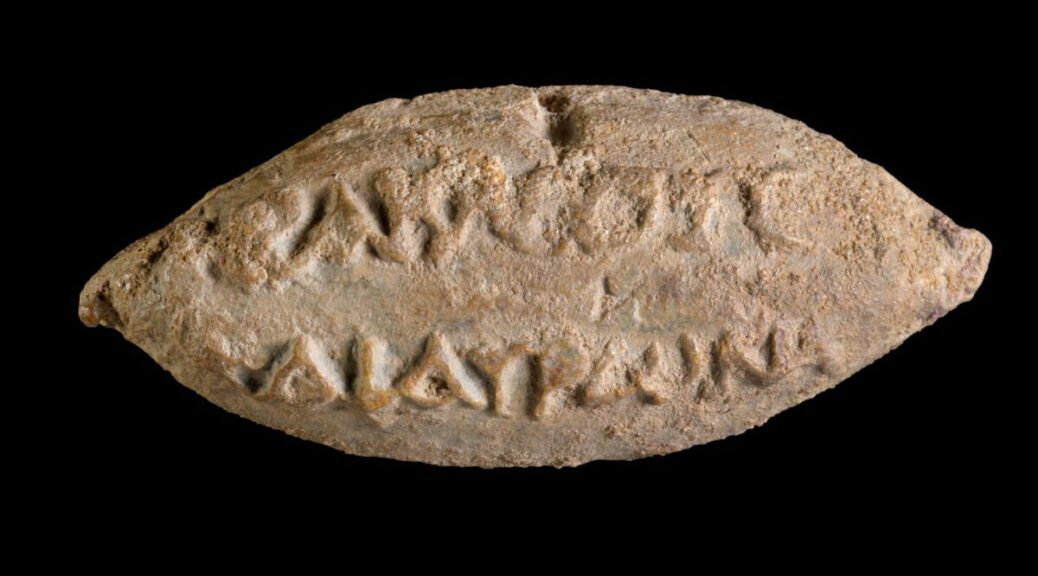

The wonders found during half a century of excavation there include the most ancient copper object in this part of the Middle East (there’s somewhat older in Iraq), a clay model of a grain silo – possibly indicating ritual involving food cultivation and storage – and a stamped sealing from around 7,000 years ago. This all suggests, the archaeologists surmise, that Tel Tsaf was an extraordinarily wealthy place as Late Neolithic settlements went.

Now Liu, Rosenberg and colleagues have detected cotton microfibers, at least some of which were dyed, from 7,000 years ago. This may provide further indication of trading relationships at the cusp of the transition from the Late Neolithic to the Early Chalcolithic in the valley.

It bears adding that the earliest cotton reported previously was in Dhuweila, eastern Jordan, and dates to centuries later – sometime between 6,450 years ago to around 5,000 years ago.

To be clear, it isn’t that humans strolled around in the altogether with their bits flapping in the breeze until discovering the delights of cotton. The thinking, says Rosenberg, is that the earliest garb was animal skins, whether worn to preserve modesty, for reasons of status, for warmth or for some other reason.

But hmo-kind discovered plant fibers at least tens of thousands of years ago. In 2020, archaeologists found no less than three-ply cord in a Neanderthal context in France, taking the crown from 23,000-year-old string found in Ohalo, Israel. What the Neanderthals or humans from Ohalo were doing with string, we do not know. However, the archaeologists note that the ability to create cord is the prerequisite for a host of potential developments, including textile weaving.

Textiles do not preserve well in the archaeological record, to put it mildly. Yet moving on from the Ohalo cord, evidence of early weaving pops up here and there – including an extremely complex woven basket found in a cave in the Judean Desert from 10,500 years ago. Material made of oak bast (the innards of bark), meanwhile, was found in Çatalhöyük, Turkey, from 8,500 years ago.

In short, before cotton, people in the region were using bast and flax fibers. And now Liu, Rosenberg and the team report on cotton in Tel Tsaf – definitely from afar, and seemingly before the plant had even been domesticated. And it was dyed, to boot.

What colors were the fibers tinted, and can they speak to Neolithic tastes? They cannot. Rosenberg stresses that the sample of fibers from Tel Tsaf is small (123 microfibers in total), and 16 being observed to be cotton in shades of blue, three pink, one purple, one green and three brown/black means precisely nothing about their preferences. What it does mean, the professor qualifies, is that these late prehistoric peoples were not just making textiles and fibers – they were doing further manipulation and coloring their cloths.

By the way, the most frequently used fiber in ancient Tel Tsaf was bast, and they also used flax and jute, the archaeologists report.

A story from Pakistan

Let us move onto the cotton’s origin. Why couldn’t the cotton fibers of Tel Tsaf be local? And why do they think it’s Pakistan, not North Africa?

It isn’t likely to have been grown locally because cotton is happiest in tropical and subtropical regions with ample water. It apparently didn’t grow in prehistoric Israel, and the thinking is that like the “invention” of agriculture itself – the cultivation of cotton arose independently around the world, including in the Indus Valley and North Africa. “But cultivation in North Africa was later,” Rosenberg explains.

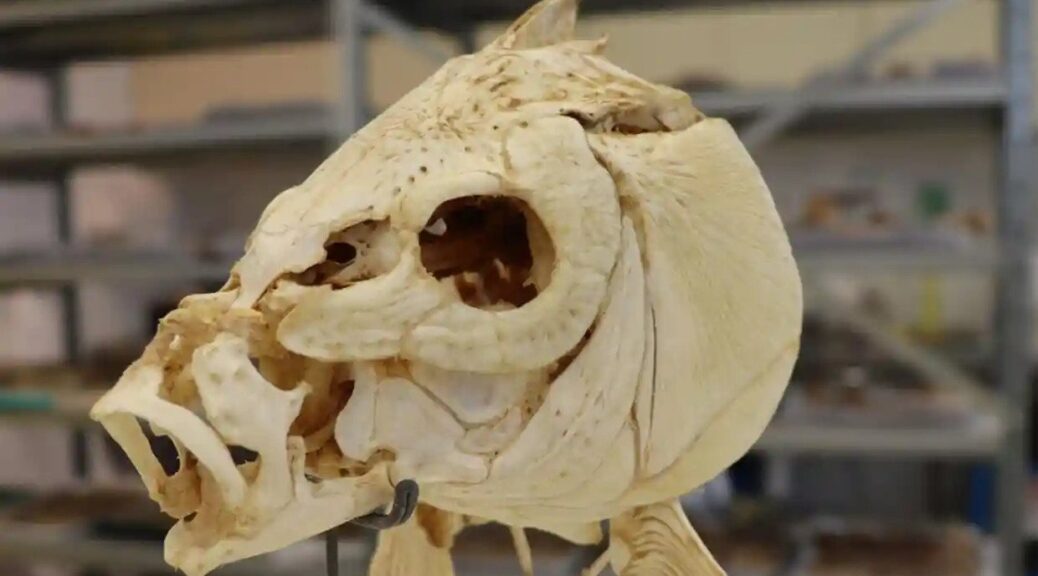

The earliest archaeological evidence of cotton’s use is in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period at the Mehrgarh burial site in central Balochistan, Pakistan. Cotton threads were used to string copper beads about 8,500 to 7,500 years ago. It bears clarifying that the earliest known cotton fabric is a tiny fragment of actual cloth (albeit stuck to the lid of a silver vase), which was discovered at Mohenjo-daro, also Pakistan, from 5,000 to 4,750 years ago.

So, cotton was known in some context in prehistoric Pakistan at the time of its appearance in Tel Tsaf, Rosenberg says.

What cotton? Wild cotton. The plant apparently wouldn’t be domesticated for at least 2,000 years more, he explains. “Based primarily on evidence from seeds, domestication is thought to have occurred during the time of the Harappan civilization (2600-1900 B.C.E.),” the authors write.

And how might the wild cotton have been used, aside from making threads to string crude copper beads? Weaving textiles is a reasonable assumption, because cotton isn’t the stuff for baskets. As for another clothing source staple, the sheep did join our human story about 10,000 years ago, in parallel with the start of the Neolithic Revolution. However, the archaeological record of perishables is spotty at best and the earliest recognition of the charms of wool as opposed to mutton stew is not clear. Some think wool-shearing and related technology arose in the Chalcolithic; some think that in Mesopotamia it began as much as 9,000 years ago.

The invisible technology

Now let us confuse the issue. Archaeological evidence of microfibers – mainly bast but wool too – have been detected going back tens of thousands of years: for instance, in 30,000-year-old Upper Paleolithic deposits in Georgia, and from 28,000 to 13,500 years ago in northern China. Traces of bast have been found in the weird Natufian “boulder mortars” in Israel’s Rakefet Cave from about 13,000 years ago. Uses of these fibers remain mysterious, ditto the mortars.

The thing is that in contrast to stone tools and even bones, textiles decay really fast under most circumstances. It’s extraordinary for any of this “invisible technology” to survive the eons, Rosenberg says. One of the earliest examples of real-McCoy fabric was found in the so-called warrior’s grave by Jericho, from the late Chalcolithic or Early Bronze Age. He was buried with a bow and a big piece of fabric.

As for the thought that the cotton could have reached Tel Tsaf by trade thousands of years before the horse was domesticated – it isn’t a stretch. An obsidian blade originating in Turkey was found in a Neolithic settlement next to Jerusalem from 9,000 years ago and other examples of ancient stuff being where it shouldn’t abound. Asked if there’s any evidence whatsoever of trade between Tel Tsaf specifically with prehistoric Pakistan, Rosenberg has an intriguing answer: maybe.

“The only thing is beads made of olivine crystals, which we think were from Africa from around 7,000 years ago. Chemical testing shows they’re like olivine in Africa – but olivine also exists in Pakistan,” he says. “Maybe we were wrong and the olivine was from Pakistan.” Tel Tsaf also has obsidian beads hailing from Turkey and there’s also that ancient copper artifact: its origins aren’t clear, but they think it’s probably Anatolian.

“Trade” doesn’t have to mean that merchants were walking from Tel Tsaf to Anatolia or Baluchistan; artifacts may change hands over centuries before being lost or otherwise winding up in ruins that we thrill at finding thousands of years later.

In the late Neolithic and early Chalcolithic, there were massive movements of peoples, and there may have been good reason why Tel Tsaf was so prosperous in that early time – hundreds of years before metals and other accoutrements of advancing civilizations would seriously arrive. It was smack on the route of long-distance exchange networks in the southern Levant. Including, maybe, with the Indus Valley.