Scientists discover 4 new Nazca Geoglyphs using AI deep learning

Scientists from Japan used AI deep learning to discover new geoglyphs in the Arid Peruvian coastal plain, in the northern part of Peru’s Nazca Pampa.

The research has been ongoing since 2004 by a team from Yamagata University, led by Professor Makato Sakai. Yamagata University has been conducting geoglyph distribution surveys using satellite imagery, aerial photography, airborne scanning LiDAR, and drone photography to investigate the vast area of the Nazca Pampa covering more than 390 km2.

The Nazca Lines are thought to have been made over centuries, starting around 100 BC by the Nazca people of modern-day Peru. They were first studied in detail in the 1940s, and by the time they were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, around 30 were identified.

They’re remarkably well-preserved considering their age, helped by the desert’s dry climate and winds that sweep away the sand but are being obscured by floods and human activity.

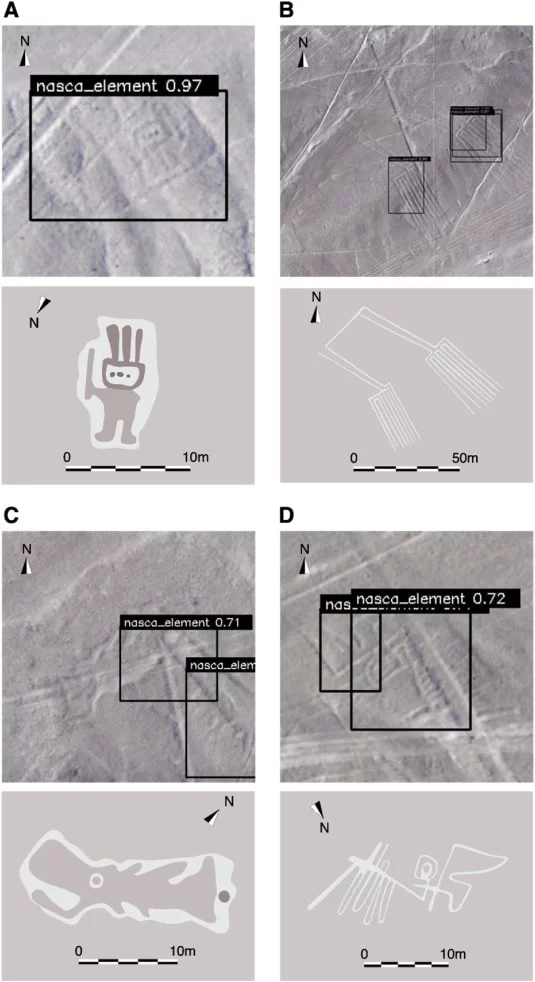

Archaeologists discovered 142 new designs in the desert over the course of ten years by manually identifying them using aerial photography and on-site surveying. Then, in collaboration with IBM Japan researchers, they used machine learning to search the data for designs that had been missed in previous studies.

In order to create a thorough survey of the area in 2016, the researchers used aerial photography with a ground resolution of 0.1 m per pixel.

The team has identified numerous geoglyphs over time, but because the process takes a long time, they have turned to AI deep learning to analyze the images much more quickly.

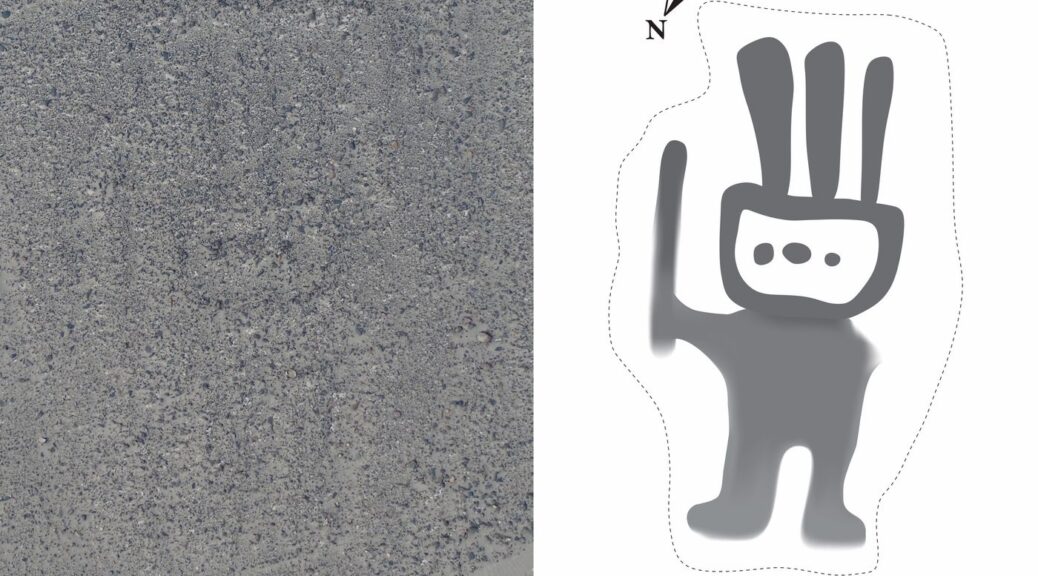

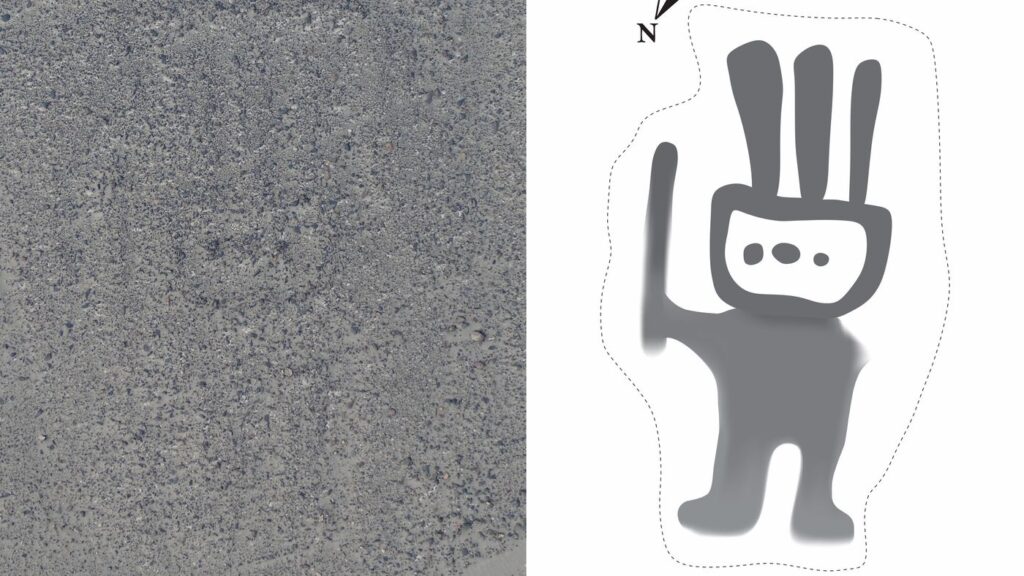

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science revealed the discovery of four new Nazca geoglyphs using this new method by developing a labelling approach for training data that identifies a similar partial pattern between the known and new geoglyphs.

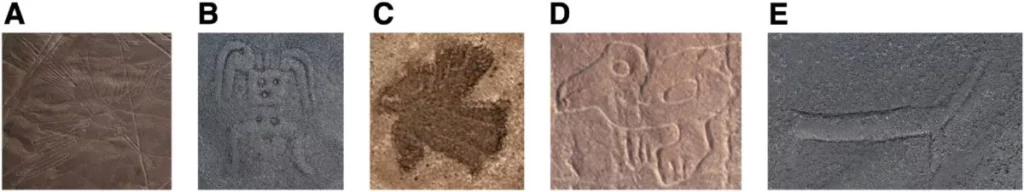

The four new geoglyphs depict a humanoid figure, a pair of legs, a fish, and a bird.

The humanoid geoglyph is shown holding a club in his/her right hand and measures 5 metres in length. The fish geoglyph, shown with a wide-open mouth measures 19 metres, while the bird geoglyph measures 17 metres and the pair of legs 78 metres.

“We have developed a DL pipeline that addresses the challenges that frequently arise in the task of archaeological image object detection,” the study’s authors write.

Our method enables the discovery of previously unattainable targets by enabling DL to learn representations of images with better generalization and performance.

Additionally, by speeding up the research process, our approach advances archaeology by introducing a novel paradigm that combines field research and AI, resulting in more effective and efficient investigations.

These results serve as yet another illustration of how machine learning can be useful to scientists, particularly when tackling tasks involving sizable datasets. Just like humans, algorithms can be taught to sift through specific types of data looking for patterns and anomalies.

Although creating these tools can be challenging, once trained, such algorithms are tireless and consistent.