Tartan Recovered From Scottish Bog Dated to the 16th Century

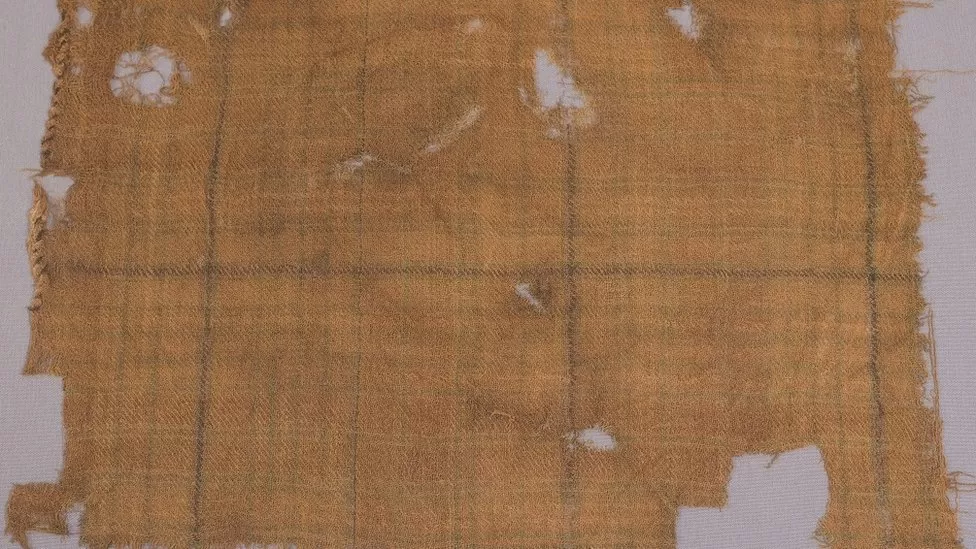

A scrap of fabric found in a Highland peat bog 40 years ago is likely to be the oldest tartan ever discovered in Scotland, new tests have established.

The fabric is believed to have been created in about the 16th Century, making it more than 400 years old. It was found in a Glen Affric peat bog, in the Highlands, in the early 1980s.

The Scottish Tartans Authority (STA) commissioned dye analysis and radiocarbon testing of the textile to prove its age. Using high-resolution digital microscopy, four initial colours of green, brown and possibly red and yellow were identified.

The dye analysis confirmed the use of indigo or woad in the green but was inconclusive for the other colours, probably due to the dyestuff having degraded.

No artificial or semi-synthetic dyestuffs were involved in the making of the tartan, leading researchers to believe it predates the 1750s.

Experts have said the tartan was more than likely worn as an “outdoor working garment” and would not have been worn by royalty.

The STA said the textile was created somewhere between 1500 and 1655, but the period of 1500 to 1600 was most probable.

This makes it the oldest known piece of true tartan discovered in Scotland.

Peter MacDonald, head of research and collections at the STA, said the testing process took nearly six months but that the organisation was “thrilled with the results”.

“In Scotland, surviving examples of old textiles are rare as the soil is not conducive to their survival,” he added.

“The piece was buried in peat, meaning it had no exposure to air and it was therefore preserved.”

He said that because the tartan contains several colours, with multiple stripes, it corresponds to what would be considered a true tartan.

Mr MacDonald said: “Although we can theorise about the Glen Affric tartan, it’s important that we don’t construct history around it.

“Although Clan Chisholm controlled that area, we cannot attribute the tartan to them as we don’t know who owned it.”

Historical significance

He also said that the potential presence of red, a colour that Gaels consider a status symbol, is interesting because the cloth had a rustic background.

“This piece is not something you would associate with a king or someone of high status, it is more likely to be an outdoor working garment,” he added.

John McLeish, chair of the STA, said the tartan’s “historical significance” likely dates to the reigns of King James V, Mary Queen of Scots or King James VI/I – between 1513 and 1625.

Due to where it was found, the piece of fabric has been named the Glen Affric tartan and measures about 55cm by 43cm (approximately 22 by 17 inches).

It will go on public display at the V&A Dundee design museum from 1 April until 14 January next year.

James Wylie, the curator at V&A Dundee, said: “We knew the Scottish Tartans Authority had a tremendous archive of material and we initially approached them to ask if them if they knew of any examples of ‘proto-tartans’ that could be loaned to the exhibition.

“I’m delighted the exhibition has encouraged further exploration into this plaid portion and very thankful for the Scottish Tartans Authority’s backing and support for uncovering such a historic find.”

He added that it was “immensely important” to be able to exhibit the Glen Affric tartan and said he was sure visitors would appreciate seeing the textile on public display for the first time.