A Hidden Underground Chamber Has Been Found in The Palace of Emperor Nero

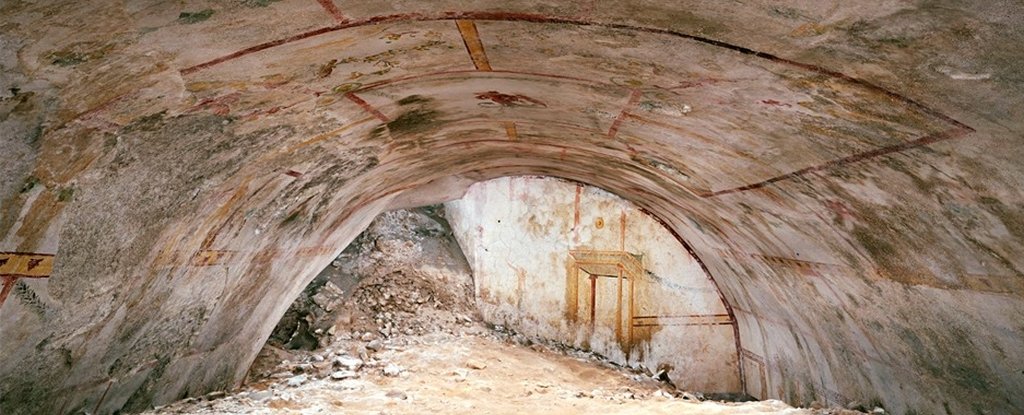

The grand, sprawling palace built by the Roman Emperor Nero nearly 2,000 years ago has been kept a secret. While working on restorations in 2019, archaeologists found a secret chamber – a large underground room decorated with murals depicting both real and mythical creatures.

In red and ochre hues, with traces of gilding, centaurs dance across the walls with depictions of the goat-legged god Pan, some bearing musical instruments.

Birds and aquatic creatures, including hippocampi, are also depicted, and a warrior armed with a bow, shield, and sword fighting off a panther, all framed by plant elements, and arabesque figures.

And the creature for which the room is named – a “silent and solitary sphinx” above what seems to be a Baetylus, a type of sacred stone.

The so-called Sphinx Room was discovered quite by accident as part of the ongoing restoration of the palace, named the Domus Aurea, or “Golden House”.

Built after the Great Fire of Rome that ravaged the city over the course of nine days in 64 CE, the palace was an opulent building consisting of 300 rooms that sprawled across the Palatine, Esquiline, Oppian, and Caelian Hills, covering up to over 300 acres.

Nero was not well-loved in his lifetime. He was cruel and tyrannical with those around him, yet lived extravagantly. His ostentatious palace was, therefore, something of an embarrassment to his successors following his death by assisted suicide in 68 CE, after his people revolted.

Significant pains were made to obliterate any traces of the Domus Aurea. Parts of it were built over – one of these structures is the famous Colosseum – others are filled with dirt.

Excavating and restoring it has been an ongoing project by the Parco Archeologico del Colosseo – the Palatine Hill section was just opened to the public for the first time ever earlier this year.

The archaeologists were working in an adjoining room in the section on Oppian Hill when they found the Sphinx Room.

They had mounted the scaffolding and turned on the bright lights they need to work – which flooded into an opening in the corner of the room, through which “appeared the entire barrel vault of a completely frescoed room,” according to a statement from the Parco Archeologico del Colosseo.

Much of the room is still filled with dirt, covering parts of the walls and very likely sections of the mural. However, there are no plans to excavate it at this time, since removing the dirt could destabilize the entire complex.

But, even under the rubble, the room is a valuable snapshot of the days of one of Rome’s most hated rulers.

“In the darkness for almost twenty centuries,” said Parco director Alfonsina Russo, “the Sphinx Room … tells us about the atmosphere from the years of the principality of Nero.”