3,000-year-old human skeleton found in Romanian archaeological site

A 3,000-year-old human skeleton was recently discovered at an archaeological excavation site in the village of Drăguşeni, Botoşani county.

The skeleton dates back to the beginning of the Bronze Age and to the Yamnaya culture, and was identified after exploring a large tumulus in Drăguşeni, according to Adela Kovacs, the head of the archaeology section of the Botoşani County Museum.

“The research in Drăguşeni focused on several periods and multiple sites. We carried out surface research in the area starting in 2018. During a field visit with colleagues from the Institute of Archaeology in Iași, we identified the remains of two large, flattened tumuli, burial monuments, that were becoming increasingly damaged due to agriculture, and we recently decided to study them.

We primarily focused on recovering scientific information and documenting the remains, and so far we have identified only one skeleton.

The skeleton dates back to the beginning of the Bronze Age and the Yamnaya culture, which is not well known in Botoșani county,” Adela Kovacs told Agerpres.

The digging in Drăguşeni was carried out by a team composed of archaeologists from the Botoșani County Museum, in partnership with archaeologists and anthropologists from the Archaeological Institute of Iași, as well the University of Opava and the Silesian Museum in the Czech Republic.

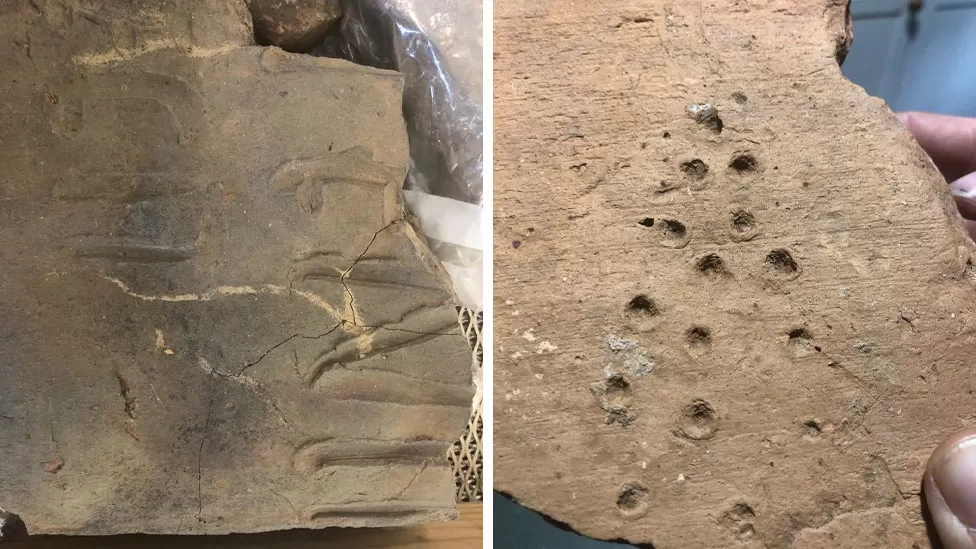

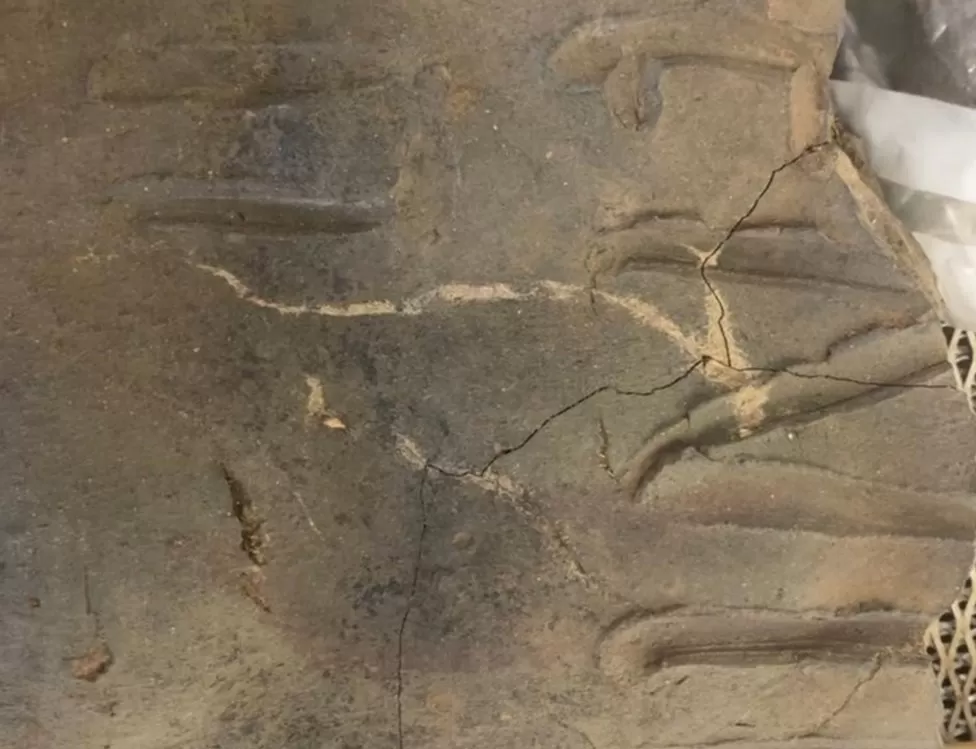

Specialists say that the skeleton “provides very valuable information with regards to the funerary rituals practiced at that time,” and note that “the skeleton bears traces of red ochre, a substance that was placed on the deceased, in the head and in the leg areas, to emphasize a ritual related to rebirth, blood, and the afterlife.

“The body’s position is curled. Initially, it was placed on its back, with the knees brought to the chest, suggesting a fetal position. This baby position represents the return to earth through a future birth,” ” said the head of the archaeology section of the Botoșani County Museum.

According to Kovacs, the entire Botoșani county has numerous tumuli. “The Drăgușeni area in particular was preferred by certain prehistoric communities when it came to burying those who were their leaders, probably, because these tumuli are funerary prestige elements.

The fact that a certain community dug the grave and built these tombs and covered them with actual artificial hills probably signaled to other populations the fact that those buried were top leaders or important people of the community,” she explained.

The skeleton was dug out, lifted, and transferred to Iași, where, following an analysis, anthropologists will determine its exact age, sex, diet, or other anthropological elements.