Saqqara Secrets: A Book Of The Dead Was Found Near Step Pyramid

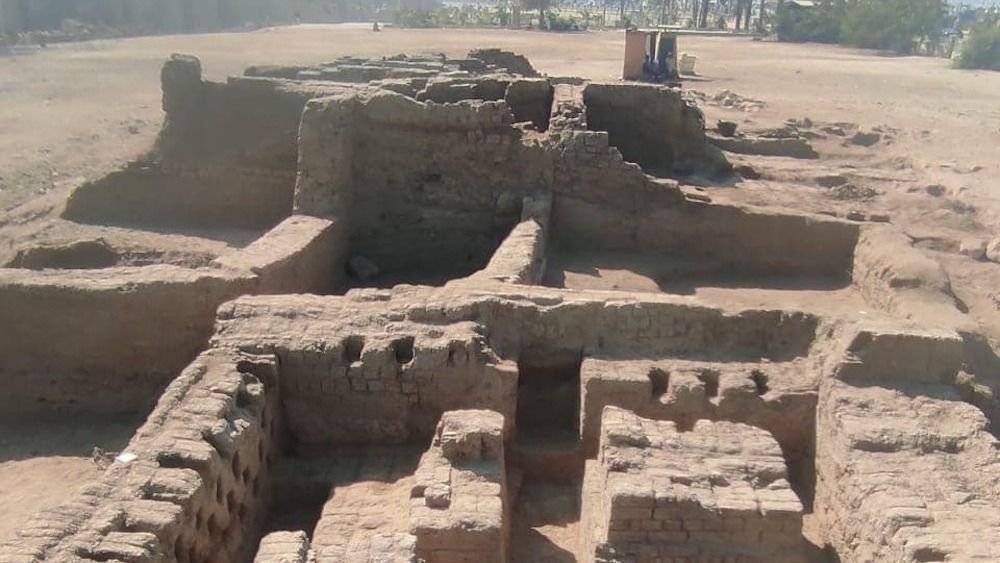

Archaeologists in Egypt have discovered a 52-foot-long (16 meters) papyrus containing sections from the Book of the Dead. The more than 2,000-year-old document was found within a coffin in a tomb south of the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara.

There are many texts from The Book of the Dead, and analysis of the new finding may shed light on ancient Egyptian funerary traditions.

Conservation work is already complete, and the papyrus is being translated into Arabic, according to a translated statement, which was released in conjunction with an event marking Egyptian Archaeologists Day on Jan. 14.

This is the first full papyrus to be uncovered at Saqqara in more than 100 years, Mostafa Waziry, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said, according to the statement.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser was constructed during the reign of the pharaoh Djoser (ruled circa 2630 B.C. to 2611 B.C.) and was the first pyramid the Egyptians built.

The area around the step pyramid was used for burials for millennia. Indeed, the coffin that housed the newfound papyrus dates to the Late Period (circa 712 B.C. to 332 B.C.), Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former minister of Antiquities, told Live Science in an email. Information about who owned the papyrus and its precise date will be announced soon, Hawass said.

The Book of the Dead is a modern-day name given to a series of texts the Egyptians believed would help the dead navigate the underworld, among other purposes. They were widely used during the New Kingdom (circa 1550 B.C. to 1070 B.C.).

While 52 feet is lengthy, there are other examples of Book of the Dead papyri of that length or longer. “There are many manuscripts that would have been similar in length, but papyrus manuscripts of ancient Egyptian religious texts can vary quite dramatically in length,” Foy Scalf, the head of research archives at the University of Chicago, told Live Science in an email. Scalf, who was not involved in the latest discovery but holds a doctorate in Egyptology, noted that there are Book of the Dead scrolls that measure over 98 feet (30 m) long.

Second papyrus

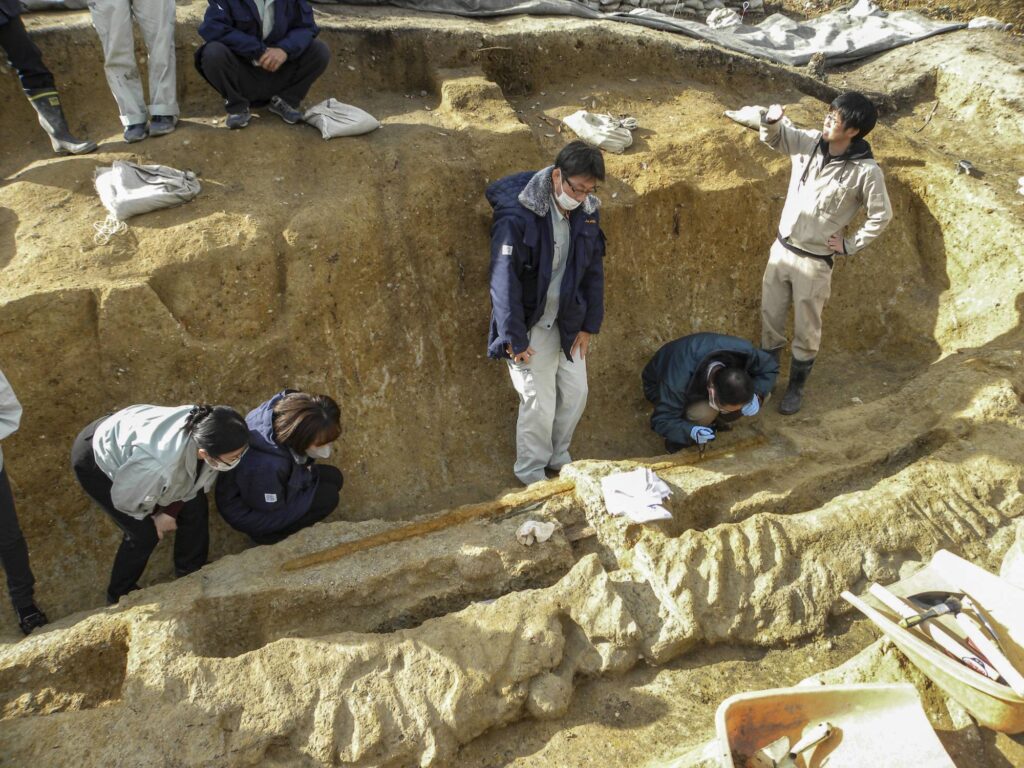

This appears to be the second papyrus containing texts from the Book of the Dead that has been found at Saqqara in the past year. In 2022, a 13-foot-long (4 m) fragmentary papyrus containing texts from the Book of the Dead was found at Saqqara in a burial shaft near the pyramid of the pharaoh Teti (reigned circa 2323 B.C. to 2291 B.C.). It had the name of its owner, a man named “Pwkhaef,” written on it.

Despite being buried near pharaoh Teti’s pyramid, Pwkhaef lived centuries after the ruler.

The burial shafts where this papyrus was found date to the 18th and 19th dynasties of Egypt (1550 B.C. to 1186 B.C.). But the practice of being buried next to the pyramid of a former ruler was popular in Egypt at the time.

The discovery was made by a team of Egyptian archaeologists from the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, which has yet to release images of the ancient document. According to the statement, the papyrus will soon go on display in an Egyptian museum.