99-Million-Year-Old Millipede Trapped In Amber Discovered In Myanmar

The analysis of an amber-trapped, 99 million-year-old fossilized millipede is bringing scientists to utterly rethink the evolution of the entire millipede species.

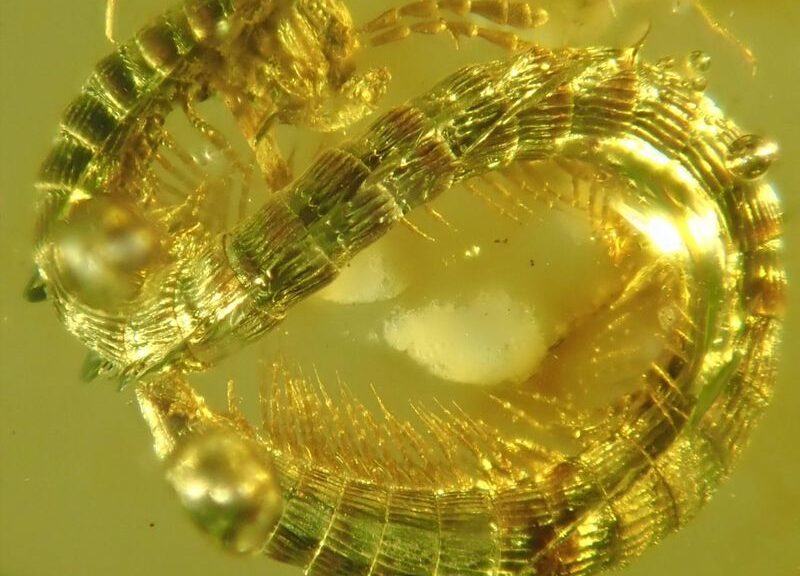

Researchers found that the perfectly preserved 8.2 mm specimen found in Burma was an entirely new species, according to a study published in the journal ZooKeys, due to its peculiar morphology that differed greatly from existing millipede classifications.

Professor Pavel Stoev at the Bulgarian National Natural History Museum told us in a statement that “We were very surprised that this animal can not be placed into the present Millipede classification.

“Even though their general appearance has remained unchanged in the last 100 million years, as our planet underwent dramatic changes several times in this period, some morphological traits in Callipodida lineage have evolved significantly.”

As a result of this exciting find, Stoev together with his colleagues Dr. Thomas Wesener and Leif Moritz of the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig in Germany had to revise the current millipede classification and introduce a new suborder for the specimen. There have only been a handful of millipede suborders described in the last five decades.

To get a more accurate look at the fossilized millipede’s morphology, researchers used 3D X-ray microscopy to construct a virtual model of the ancient millipede, including its internal features.

The examination showed that the 99 million-year-old millipede was, in fact, significantly different from other early millipede species. The researchers named the new species Burmanopetalum inexpectatum, with the latter word meaning “unexpected” in Latin.

Among the Burmanopetalum inexpectatum’s unique traits are its eye, which is composed of five optical units where other millipede orders usually have but two or three.

Another fascinating trait of the newly discovered millipede is its smooth hypoproct, which is the spot located in between the anal opening and the genitalia of an insect.

By comparison, its younger brethren usually have hypopcrocts that are covered in bristles. These highly unusual traits have given scientists a completely new perspective regarding how its kind evolved.

Not to be confused with centipedes, millipedes belong to the Diplopoda class which is Latin for “double foot.” The name refers to the two pairs of legs that these critters have on each of their body segments in addition to its many tiny legs. By comparison, centipedes have only one pair of legs per body segment.

Also unlike centipedes, millipedes are not active predators and they survive on a diet of decaying plant matter. When threatened, millipedes will secrete poisonous chemicals to deter animals that may want to hurt or eat them.

Scientists estimate that there are 80,000 species of millipedes, yet only a fraction have been discovered and studied.

This ancient insect’s peculiar characteristics are not the only thing that sets it apart, however. The fact that it was discovered in Myanmar is also significant because scientists have never discovered a Callipodidan in Myanmar before, which means that this order of insects must have existed in the Southeast Asian region as well.

The Burmese amber that the millipede had been trapped in was part of a private collection of animals that belonged to Patrick Müller.

This collection included 400 amber stones that the scientists had been granted access to, and is the largest collection of its kind in Europe and the third-largest in the world.

Much of the collection is now deposited at the Museum Koenig in Bonn, Germany, where other researchers from around the world may gain access to study the collection, too.