Pottery Residues Reveal Changes in Central China’s Neolithic Diet

The sustainable development of agriculture has laid a solid foundation for the birth of human civilization and countries. Early agriculture has long been a focus of archaeology.

China is the only country in the world with two independent agricultural systems, that is, rice farming in the south and millet farming in the north.

Research has shown that rice farming prevailed in Jianghan Plain in the Neolithic period, and the millet from the north spread to the region no later than the Youziling Culture period (5800-5100 BP).

Nevertheless, it remains to be unveiled what other plant foods were consumed by prehistoric people and how the paleodiet of plant foods evolved.

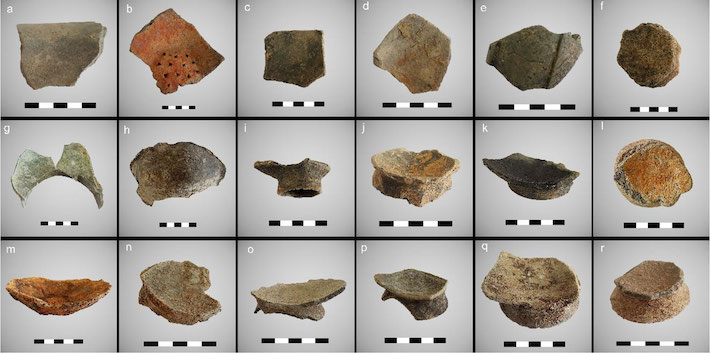

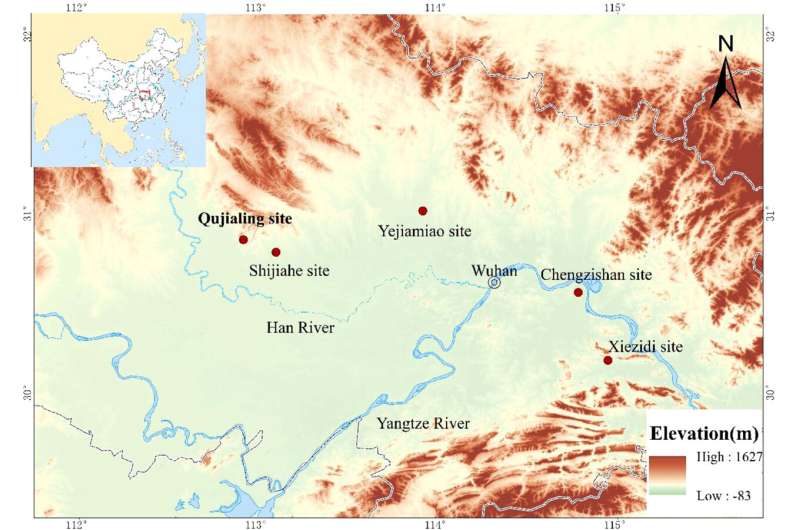

In a recent study published in Frontiers in Plant Science, a research team led by Prof. Yang Yuzhang from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has, for the first time, applied starch grain analysis to examine pottery sherds from the Neolithic site of Qujialing, and revealed the resources and structure of plant foods consumed by prehistoric people in the research region.

The researchers detected starch grains from the species including job’s tears (Coix lacryma-jobi), lotus roots, acorns, Chinese yam, and legumes on the Qujialing pottery vessels, apart from rice and millet that had been previously identified, indicating the obvious diversity of plant food resources in the late Neolithic period.

Notably, job’s tears and lotus roots in the archaeological work at Qujialing were first identified.

The high frequency of detecting starch grains from lotus roots showed that they had been widely consumed by Chinese ancestors, and that might be related to the local environment surrounded by water with abundant aquatic plant resources.

Based on the findings of previous work on macrofossil remains and phytoliths and by quantitative analysis of the frequency of various starch grains of different phases, the researchers confirmed that rice persistently dominated the paleodiet, and the proportion of food like acorns procured from gathering significantly decreased as agriculture developed in the Qujialing site.

This study unveiled the economic characteristics and dietary change in the middle catchment of the Yangtze River Basin in Neolithic times, and shed new light on the spread of millet and other crops from the north to south.