Siberian Princess reveals her 2,500-year-old tattoos

Tattoos aren’t just a trendy way for people to express themselves – they’re also apparently a time-honored tradition dating back almost three thousand years.

A Siberian mummy, who researchers believe was buried 2500 years ago, will show off her intricate ink when she finally goes on display this month, and her shockingly well-preserved body art makes her look surprisingly modern.

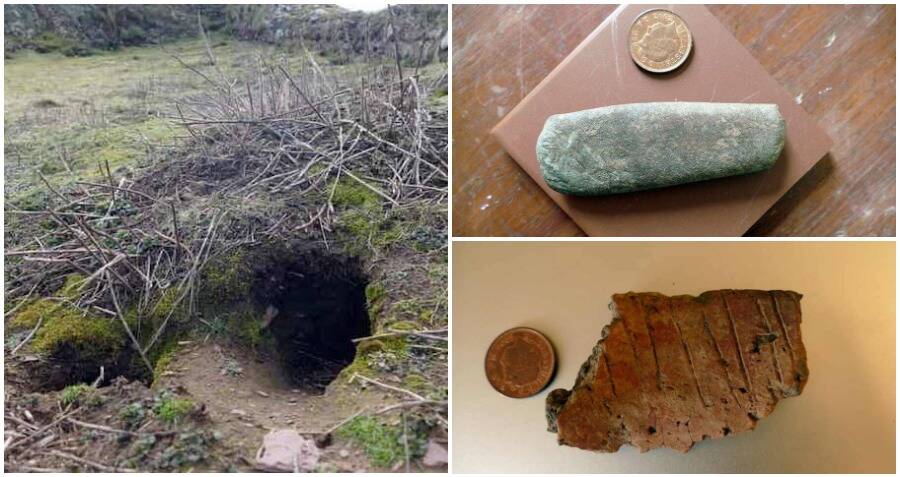

The mummified body of the young woman, believed to be between 25 and 28 years old, was found in 1993, researchers told The Siberian Times.

Since then she has been kept frozen in a scientific institute, but she will soon be available to the public to be viewed from a glass case at the Republican National Museum in Siberia’s capital of Gorno-Altaisk.

The woman, dubbed in the media as the Ukok “princes,” was found wearing expensive clothing – a long silk shirt and beautifully decorated boots – as well as a horse hair wig.

Archeologists told the paper that because she was not buried with any weapons she was not a warrior, and that she was likely a healer or storyteller.

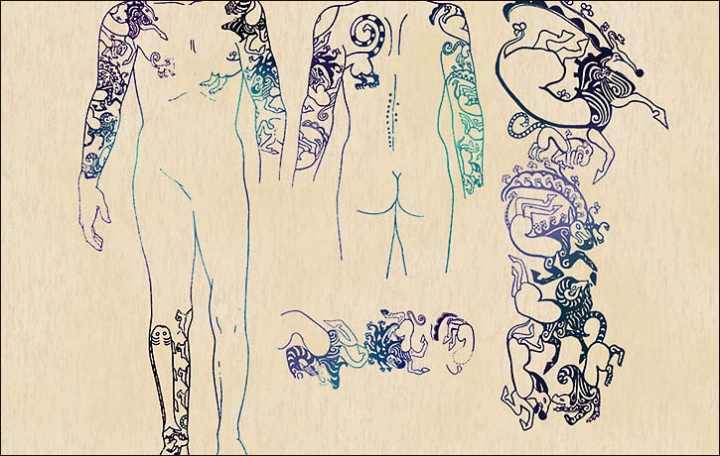

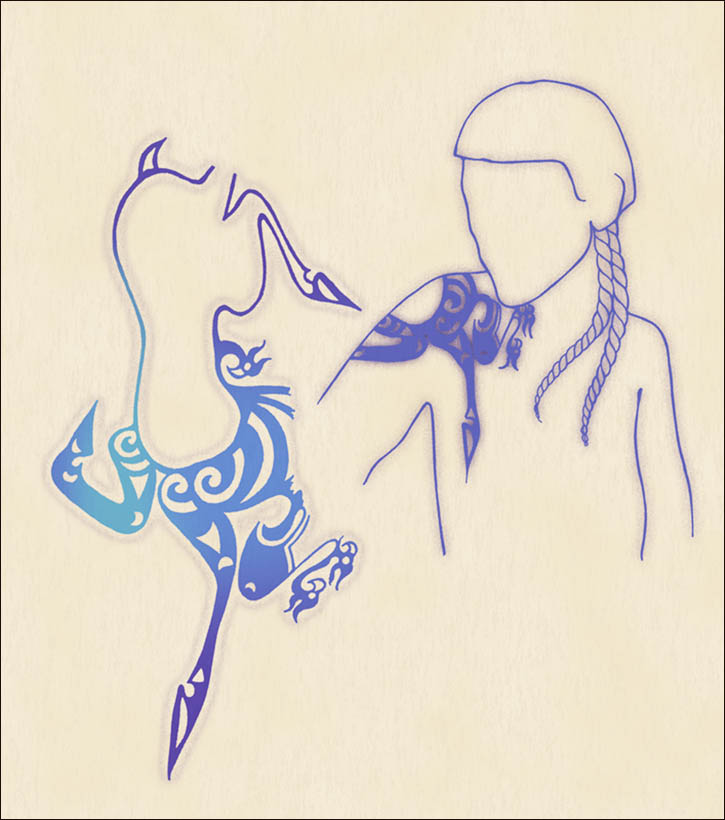

Though her face and neck weren’t preserved, she was inked across both arms and on her fingers, in what researchers say was an indication of status.

“The more tattoos were on the body, the longer it meant the person lived, and the higher was his position,” lead researcher Natalia Polosmak told the Times.

The woman was buried beside two men whose bodies also bore tattoos, as well as six horses.

Researchers think the group belonged to the nomadic Pazyryk people, and that their body art is something special even in comparison to other mummies who have been found wih tattoos in the past.

“Those on the mummies of the Pazyryk people are the most complicated and the most beautiful,” Polosmak told the Times.

“It is a phenomenal level of tattoo art,” she said. “Incredible.”

Not everyone was pleased that the mummy was uncovered.

Controversy erupted after she was discovered, as many believed she should not have been removed from her burial site. Some locals even believed her grave’s disruption caused a “curse of the mummy” which they blamed for the crash of the helicopter carrying her remains.

“The Altai people never disturb the repose of the interned,” Rimma Erkinova, deputy director of the Gorno-Altaisk Republican National Museum told the Times. “We shouldn’t have any more excavations until we’ve worked out a proper moral and ethical approach.”

Local authorities in the region have declared the area a ‘zone of peace,’ so no more excavations can be done in an effort to prevent plundering, though scientists believe there are many more mummies that can be found.