A 42,000-year-old pendant found in northern Mongolia may be the earliest known phallic art

An international team of researchers has found a pendant in northern Mongolia that may be the earliest known example of a carved phallus. This pendant suggests that for at least 42,000 years, our species has been artistically depicting the penis.

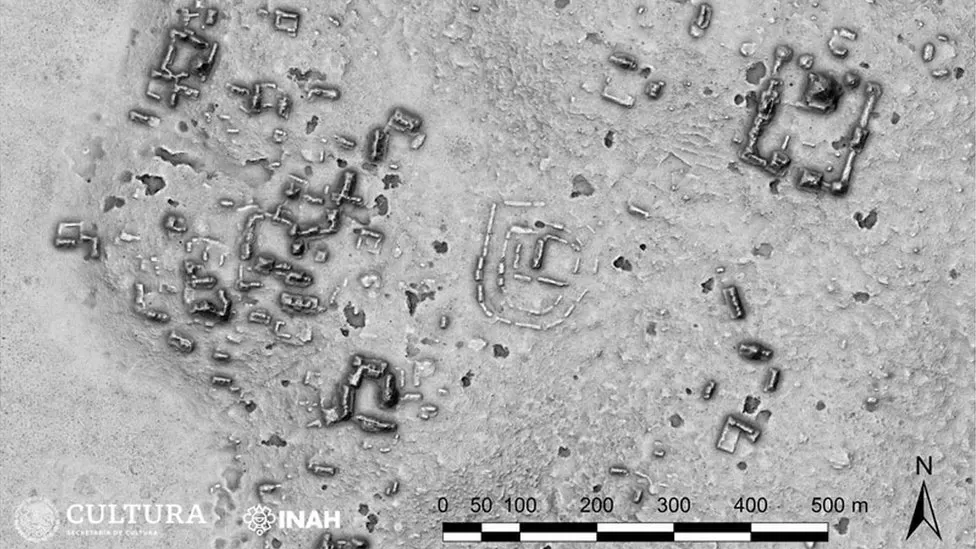

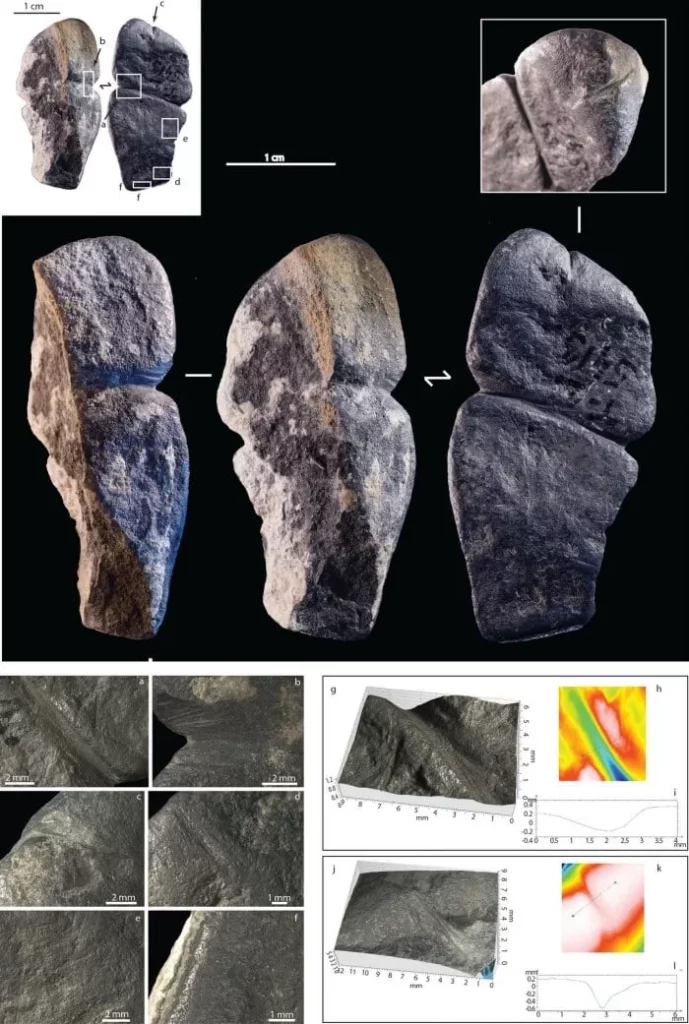

The stone was found at a dig site in northern Mongolia’s Khangai Mountains. The piece of ornament interpreted as a phallus-like representation is about 4.3 centimeters long and made by humans.

According to researchers behind a study of the pendant, published this week in Nature Scientific Reports, the carved graphite is the “earliest-known sexed anthropomorphic representation.”

The dating of the material shows it was from approximately 42,400 to 41,900 years ago, putting its creation in the Upper Paleolithic.

Three-dimensional phallic pendants are unknown in the Paleolithic record. It attests that hunter-gatherer communities used sex anatomical attributes as symbols at a very early stage of their dispersal in the region.

The pendant was produced during a period that overlaps with age estimates for early introgression events between Homo sapiens and Denisovans, and in a region where such encounters are plausible,” the science team wrote in the study published in Nature.

The black pendant has several grooves, but two of them caught the attention of scientists.

Researchers think these grooves were carved into the stone to make it resemble a human penis. But not everyone is convinced that the Mongolian pendant represents a phallus.

Solange Rigaud, an archaeologist at the University of Bordeaux and the study’s lead author, thinks the strongest argument for the pendant as a phallic representation comes from the features its maker focused on.

“Our argument is that when you want to represent something abstractly, you will choose very specific features that really characterize what you want to represent,” she says. For example, the carver appears to have taken care to define the urethral opening, she notes, and to distinguish the glans from the shaft.

A combination of microscopy and other surface analyses show that stone tools were likely used to carve out the grooves for both the urethra and the glans.

The pendant was also discovered to be smoother on the back than the front; a string was likely fastened around the glans, suggesting the ornament may have been worn around the neck.

The amount of wear on the surface suggests it was likely handed down across multiple generations.

Graphite wasn’t widely available near Tolbor, suggesting the pendant may have come from elsewhere, perhaps through trade.

The study was published in the journal Nature.